“I had the good fortune to have worked with and learned from some enormously talented people. Working on pictures with them was hugely instructive,” British film director Guy Hamilton (born in Paris, 1922) said in this 2003 interview, referring to people like his mentor, Academy Award-winning filmmaker Carol Reed (1906-1976), whom Mr. Hamilton was able to collaborate with during the very early stages of his career. Indeed, they may have shown him the way, they may even have paved the way, but his finishing touch was all the more remarkable. There’s so much to recommend Mr. Hamilton’s films; for nearly four decades, ever since his directorial debut with the entertaining mystery thriller “The Ringer” (1952, based on Edgar Wallace’s novel), he was one of industry’s leading and most expressive mainstream film directors. As a director, he was able to come up with first-class, rousing adventures, with four Bond films, including two of the best, “Goldfinger” (1964) and “Diamonds Are Forever” (1971); war films as “The Devil’s Disciple” (1959), an adaptation of George Bernard Shaw’s 1897 comedy, set in New England at the time of the War for Independence, starring Burt Lancaster, Kirk Douglas, and Laurence Olivier in the plum role of Major General John Burgoyne, or “The Best of Enemies” (1961), not only a war film, but also (or merely) a comedy-drama about the respect that develops between a British and Italian Captain (played by David Niven and Alberto Sordi) in North Africa during World War II.

But there were also sparkling and refreshing comedies, such as “A Touch of Larceny” (1959) with a charming James Mason pretending to defect to the Russians; thrillers as “Funeral in Berlin” (1966), the second of three spy thrillers with Michael Caine as the bespectacled Harry Palmer forced to become a counterspy (with an interesting look of postwar Berlin), and all-star whodunits like “The Mirror Crack’d” (1980, with “Murder at Midnight,” a wonderful black & white movie-within-a-movie as one of the picture’s many original highlights), and “Evil Under the Sun” (1982) with numerous stars from the past, including Angela Lansbury, Elizabeth Taylor, Rock Hudson, Tony Curtis, Kim Novak, and Peter Ustinov. Right up until the very end of his long and fascinating career, he still demonstrated his own personal ‘Hamilton touch,’ meaning he was by far and large one of the most proficient’s craftsmen among the filmmakers of his generation, no matter what film genre he was working in.

“The Mirror Crack’d” (1980, trailer)

On top of that, Mr. Hamilton also made several remarkable films that—unfortunately, and apparently—are only remembered by film buffs at this point, and which seem to have been lost amidst the huge film output of recent decades, films like “The Colditz Story” (1955), a wonderful prisoner of war saga set in Germany’s allegedly escape-proof Colditz Castle in the heart of Saxony (based on the personal experiences of Pat R. Reid, portrayed by John Mills) or the engrossing military courtroom drama “Man in the Middle” (1964) with Robert Mitchum as a defense attorney.

A career filled with a huge string of artistic and commercial highlights, although an unexpected disappointment came late in his career when he was set to direct Christopher Reeve and an all-star cast in “Superman” (1978). Considered to become one of the largest productions of the decade and scheduled to be shot at Rome’s Cinecitta studios, plans were changed when Marlon Brando, who played Superman’s father, flatly refused to work in Italy. This happened after director Bernardo Bertolucci ran into trouble with the Italian court as a result of obscenity charges, because of “Last Tango in Paris” which they made a few years earlier. The “Superman” production switch from Rome to England (Shepperton and Pinewood studios) had huge consequences. Mr. Hamilton, who at that time had been living in Spain for a number of years, was considered a British tax exile with work restrictions in the United Kingdom, which ultimately didn’t allow him to direct the film any longer. He was replaced by Richard Donner.

It’s about time to repolish all those wonderful films he made, and let’s start with the man who made them all. It’s our pleasure to introduce you to Guy Hamilton.

Mr. Hamilton, you were born in Paris. How do you remember your childhood? Was film also a part of your childhood?

Absolutely, even though I was destined for the diplomatic corps [laughs]. I was about eight years old, I think, when I fell in love with movies. The parents of some of the children at the Paris school I went to were distributors for companies such as Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer or United Artists. As soon as we got out of school, which was at four o’clock in the afternoon, we wandered down the Champs-Elysées because we didn’t have to be back at home before six o’clock. So we’d go to all of these cinemas because the managers knew their fathers, we always walked in halfway through the film. American films were absolutely it. At school, I did a little bit of acting, but I soon found out it wasn’t my cup of tea. The cinema, more specifically the storytelling part of the cinema, really fascinated me. From the age of ten, till I was about fourteen or fifteen, a holiday was a lousy one if I didn’t see one picture a day. That’s when I learned how to tell a story: I was so passionate about the power and the impact of movies that I knew what I would do professionally in the years to come: directing films. I had a vague idea of what a director did, it was obviously a well-paid job, and it obviously meant pretty girls. I was even beaten at school when they asked me what I wanted to become and said I wanted to be a film director—it was like if you’d run a brothel. It made me more determined than ever to get involved in films. Then one afternoon, I saw Jean Renoir’s “La bête humaine” [1938, starring Jean Gabin and Simone Simon]. That absolutely knocked me out. It was as if I grew up immediately, and from that moment on, American films seemed awful; they all used the same formula. From the age of sixteen, Renoir was one of my Gods, and I just knew that’s where I wanted to make my career.

Your mind was made up, thanks to Jean Renoir, among others?

Exactly. When the War broke out, I managed to make a deal with my father to take a sabbatical year, and so I went to Nice [south of France]. I walked in the Victorine studios [now Studios Riviera], met the managing director, and said to him, ‘I’d like to be a director!’ He looked at this sort of English idiot [laughs], and I said, ‘Well, not today, but I would like to learn.’ And he offered me a job in the accounts department. At the end of the week, he came up to me and asked, ‘Well, what did you learn?’ I said, ‘Nothing at all. I only handled weight packages.’ He said, ‘No no, you’ve been with us now one week, and you discovered that apart from what directors, film stars and cameramen do, there are also other things to be done and there are other people involved as well in this whole constitution of a studio, like carpenters, gardeners, etc. Monday, you start on the floor with the camera crew.’ When I joined them the following Monday, they were delighted to see me there, they were in need of a clapper boy, someone to bring them coffee, and they also taught me how to do hand tests for the cameraman. Halfway through this exercise—for some reason—I got switched on to the sound crew. At the end of that film, I was asked again what I have learned. I said, ‘Well, I am a little confused. I thought I’d become a cameraman first because film is a visual art, but there’s also sound with the nickelodeons, and the work in the cutting rooms at night…’ And he said, ‘Good, you’ve learned the first rule if you want to be a director. All technicians are shit, and your job is to bang their heads together!’ [Laughs.] That was my introduction to the process of filmmaking.

How long did this learning experience last?

Not too long. Because of the outbreak of World War II, the British were evacuated to England by way of Cannes. It was then that I met one of my literary idols, Somerset Maugham. After my arrival in England, I worked for Paramount News which was a terrific training ground. All the newsreel companies like Paramount and Pathé cut their footage in a different way because whatever they shot, was given to everybody. To watch these editors at work… they had no basic training, and at the end of the week, there were all of these piles of film that were going to be junked, and so I used to come in on Saturdays and cut battles. When someone asked me what I was doing, I said, ‘I am learning about editing.’ [Laughs.]

What effect did World War II have on your plans for the future?

My service with the British Royal Navy brought me all over the place, from destroyers to convoys heading for Russia. I was aged eighteen then, and I grew up a great deal. What I knew was that if I came out of the War alive and well, I wanted to be in the [film] business—that’s all I wanted to do for the rest of my life. As it turned out, I was very fortunate, I came out of it in one piece and also a lot better than most of my contemporaries who were, like me, twenty-three or twenty-four, and who couldn’t go back to school. It was too late, and so they were very mixed up about what they were going to do with their careers. I knew what I wanted, but it wasn’t easy to get back in. In my absence, the unions had become very powerful, and I couldn’t get a ‘ticket’—you couldn’t get a job in the film business if you didn’t have a ticket. So I had to do quite a lot of stalling around but finally—finally—I got in as a third assistant director.

What did a third assistant director have to do?

A first assistant has two assistants, the second and the third. The third is really a teaboy; he runs for the first assistant. It’s important to have a good third, for instance, you’re forever on the set waiting to find out how advanced the leading lady is with her make-up or with her hairdo. If you’re running miles behind, as a first assistant, you’ve got to talk your director into not setting up to do the shot as the leading lady will not be there. You’ve got to chat him up, ‘Wouldn’t it be good to also do this or that?’ ‘Yes, all right!’ [Laughs.] But in the meantime, the third has bullied the leading lady, or perhaps he told her, ‘I will give you a bunch of flowers if you move on’—that’s his job. When you get crowd scenes, he’ll tell, ‘I want more people down there, fewer people up there.’ He organizes things like that. The second assistant does mostly office work; what are they going to shoot tomorrow, check if everything is there, and they get to the studio at six o’clock in the morning to make damn certain that the ladies are there too at six o’clock because they got about an hour for dressing, about an hour for make-up, and they’d better be on the set by nine o’clock—or else [laughs]!

And by then, director Carol Reed crossed your path?

And by then, director Carol Reed crossed your path?

Yes, he launched me by taking me on as his first assistant with “The Fallen Idol” [1948, a stylish and skillfully made thriller, about a child’s-eye-view of an adult world, with then nine-year-old Bobby Henrey as the boy]. The film got several awards, including the New York Film Critics Award as Best Director. A few years ago, I went to the British Film Institute, where they did an evening of “The Fallen Idol.” Bobby Henrey had come over from Canada. I didn’t recognize him; he looked very elderly and rather frail. But he has nothing to do with films anymore. Anyway, I think Carol sensed my enthusiasm, to him that seemed to be more important than experience. What I was determined to do, was not to be an assistant director but a director’s assistant because all directors have things that they care about passionately and other things they’re are less interested in—they ought to be, but they’re not [laughs]. So I’d say, ‘Fine, I’ll take care of that for you.’ ‘Oh, would you? Thank you.’ Then you make absolutely certain that you work your tail off for the things they care about. You also have to watch them, know their moves if they’re not happy, what are they not happy about—is it the performance, is it something you can help them out with… And I was devoted to Carol. He made my life easy because I followed him around like a little dog while learning my trade. If you’d ask him a question, he’d always answer it. I would get a lift back to his house in Chelsea—Shepperton was miles away from London in those days—and I’d talk to him about the films he had done, why he had done certain things, what were the most difficult things and gradually I could see how his brilliant mind was working. I made myself invaluable, there’s no question about that because for every new picture he made, long before, I was needed. He took me off to Vienna, all over the Far East on location hunting. Carol Reed was the biggest influence on me, and on everything that I did.

What were the Shepperton studios like in those days?

It was an interesting period at Shepperton back then. They used four sound stages; there was always one production on two stages, another one on the other two. Night locations were very rare because it was so expensive to light a whole street. Also, Carol and David [Lean] worked exceptionally slowly, and one day, Alexander Korda said, ‘They must really pull their socks up and work faster.’ In Hungary, Alex had made about fifty pictures, more than Carol and David made in their entire careers. They adored Alex; they had great respect for him. He made a huge contribution to the British film industry. His personality dominated Shepperton. Anybody who ever worked with Alex, worshipped him. He was more British than the British; that was something wonderful.

You made three films with Carol Reed. After “The Fallen Idol,” you did “The Third Man” [1949] and “Outcast of the Islands” [1952]. “The Third Man” is undoubtedly one of the most beloved screen classics, a simple thriller in the best Hitchcock tradition, isn’t it? How do you remember working on that amazing film?

You made three films with Carol Reed. After “The Fallen Idol,” you did “The Third Man” [1949] and “Outcast of the Islands” [1952]. “The Third Man” is undoubtedly one of the most beloved screen classics, a simple thriller in the best Hitchcock tradition, isn’t it? How do you remember working on that amazing film?

It was an extraordinary picture to make because we had three units—a day unit, a night unit, and a sewer unit, and Carol directed all three. I was his assistant, so I had to be with him all the time. How was that possible? Simply, because it was winter, it was not really daylighted till about 9 o’clock in the morning, and it got dark at about 4 o’clock. The night unit didn’t start until about 8 o’clock, so you could get a couple of hours of sleep, and they worked until about 4 o’clock in the morning. The problem was the actors. If Joe [Joseph Cotten] had worked all night, he had eight hours off between calls. In one particular scene, when Harry Lime [character played by Orson Welles] is being chased and runs through the empty streets of Vienna at night, all you see of him is his shadow on the walls, and all you hear are his footsteps—actually, that’s me. Orson was in Rome then, playing hard to get, and we were running out of work with him, bearing in mind that he had very little work to do. It was getting very difficult. So one day, Carol began to develop shadow concepts, and he asked me, ‘Guy, can you run in front of the camera and make a shadow on that wall?’ I did, but I was a skinny little bugger, so I put on a big hat, extra clothes, and a big coat. So what you see on the screen in one or two shots, I doubled for Orson.

I suppose that you and Alida Valli [1921-2006, at the time of this interview from 2003, she was still alive] are the only surviving members of the film right now, aren’t you?

I think so. Alida was invited to Vienna for the fiftieth anniversary of the film, but she didn’t turn up. I haven’t seen her since those days which I’m rather disappointed about because I would have loved to see her again, I was very fond of her. Later on, I sent her a letter, telling that I was sorry she didn’t turn up, but I didn’t get a reply. When I was in Rome in the 1970s, I was going to do “Superman” at Cinecitta where it was all set up, and I tried to contact her—in vain.

“The Third Man” (1949, trailer)

Why do you think “The Third Man” has become such as classic?

Because it’s a pretty good picture. Why do people see “Casablanca” [1942] again and again? Because it is so entertaining. Now pictures are often so slow. Although they go from cut-bang bang-cut, they’re still slow because they don’t get on with the story. We’re talking about beautifully well-made pictures here. Also, when we started, there were fade-ins and fade-outs to indicate there was another day or another place. Film directors must be gentle to the viewer’s eye. If your eyes are taken to the bottom right of the screen, the next cut can’t be half at the top end there unless you want to shock. If you look at all these great masters, they’re gentle to the eye; they make sure that when they make a cut, your eye will be taken to the next place on the screen. Now, who the hell cares… I find it very awkward. Let’s not forget that movies are visual art.

How do you look back to your experiences as a first assistant director to other filmmakers?

Some of them were bad, but in a way, you learn more from those directors. Bad directors get themselves into trouble three, four times a day. You watch them struggling to get out of their problems, and you swear that, if and when you get a chance to direct, you won’t repeat their mistakes. On “The Third Man,” Carol asked what I was going to do after the picture was over. He also said, ‘You know, it’s time for you to direct. There’s nothing else I can teach you.’ He advised me never to make the picture I really wanted to make because that’s like walking on a trapeze—if you fall off, you’ll find it very hard to make another picture. So Carol suggested to me I’d notify Alexander Korda that I wouldn’t sign a new contract as an assistant director unless he promised me a picture to direct. Three or four days later, a telegram arrived, which was handed to Carol. It said, ‘Dear Carol, you put him up to it, you bastard! Love, Alex’ [laughs].

I’m sure that your work for “The African Queen” [1951], shot on location in Africa, was an extraordinary experience as well. What kind of a director was John Huston?

I’m sure that your work for “The African Queen” [1951], shot on location in Africa, was an extraordinary experience as well. What kind of a director was John Huston?

John Huston was an interesting man to watch working because he had his own very particular style. You see, there are things that stimulate you, and his great strength made him a very good script writer; he had a very clear idea. Any script he had anything to do with, was just great. On the set, he relied very much on his script, which makes the shooting rather simple. He was not interested in flashy camera moves or anything like that, and that made the actors very comfortable. I was rather on my own, but the days on “The African Queen” were enormously primitive. We were in the Belgian Congo, and John was really keen to shoot an elephant, rather than shooting the film. That was his prime concern, and I was delighted that, when we all arrived in Kenya for location hunting, all his guns and weaponry were confiscated by customs. And for his elephants, he had to apply for a license—only about six licenses a year were issued, and there was a queue of about five years. So when we returned to the Belgian Congo, someone told him that you could shoot elephants and you didn’t need a license down there. Immediately after the production moved there, close to the river, there was a horde of elephants going around there, which John had spotted from the airplane in the air. The elephants tended to go around in circles, so he knew they’d be there by the time the unit arrived. But anyway, “The African Queen” was a tough picture to make in the sense that the art director and I had to build a camp because there were no hotels. The native women carried a bucket of water. They got a penny a bucket, and they put it in a big tank; it was all wonderfully primitive. The boat ‘The African Queen’ was much too small to shoot on, so we made four or five canoes, all thirty or forty feet long. They were joined together and on to that, we had room enough for the camera and the cameraman Jack Cardiff. The stern of ‘The African Queen’ towed this which in turn towed another pirogue where all the units sat on. There were other pontoons too—it was an enormous convoy, it was unbelievable that everything was to be towed up river by ‘The African Queen.’ I was in charge of all this. Nobody gave me any help at all. As we went around bents, we were always hooking onto something. The worst thing was Katharine Hepburn’s lavatory. It was in her contract that she had her private lavatory, so there was a little pontoon with a little hut. That was the last thing that was towed. Can you imagine this convoy of bits and pieces, and every bent that we came around, we always got tied up in the reed, in the trees, in the things that were overhanging. Whenever things fell off the convoy, we said, ‘We’ll pick it up on the way back tonight.’

What about Humphrey Bogart and Katharine Hepburn?

They were huge personalities, but they never complained. I wonder if you could do all that with the modern stars. You could never get a star like Steve McQueen anywhere near to what was going on in “The African Queen.” I remember I was in Jamaica looking for locations for one of the Bond films, and much to my surprise, I came across Tony Masters, an art director I knew well, and I helped him out, I knew where he could find what he was looking for and I told him about it. He said, ‘Oh well, I know about that place, but it’s too far from the hotel. It’s in Steve McQueen’s contract that no location can be more than ten miles from the hotel.’ I told him he had my utmost sympathy because in James Bond movies, we didn’t work that way, nor would our producers sign such a silly contract. But that is typical of the American producers of that period, and even today, they’re so panic-stricken to get a star that they’d give them caravans that would have to be flown in by helicopter. The idea of sleeping in tents—impossible, we couldn’t shoot that way! There was no question about that in those days, everybody worked harder, and it was more fun.

“The African Queen” (1951, trailer)

With “The Ringer” [1952], based on Edgar Wallace’s play, you then made your debut as a director?

Yes. Carol Reed had once been Edgar Wallace’s assistant; he had made a Wallace film, and was a great believer in Edgar Wallace [1875-1932]—after all, Wallace was the man who would hurl Reed into making pictures. Carol admired him a great deal, and so “The Ringer” was my first picture for which I had three weeks to finish. The problem after your first picture is your second one, and from the very start, I knew what I was up to. Although television was new in those days—it had no impact whatsoever because only very few people had a set. I had seen a live play on television called “Dial M For Murder” which I thought was terrific, and I knew this is what I wanted to make, it would be a terrific film. Alex bought the play for £500 and I had high hopes. But being the junior contractor, I was assigned to do all the tests with actors like Richard Burton, which interfered with my putting on a script, and during one of those tests, I heard Alex was selling “Dial M For Murder” to Hitchcock. Well, I knew I wasn’t gonna win this one [laughs].

“The Ringer” was considered a B picture, but very soon, with “The Colditz Story” [1955], you became an established and full-fledged film director. Why did you choose to make “The Colditz Story”?

“The Ringer” was considered a B picture, but very soon, with “The Colditz Story” [1955], you became an established and full-fledged film director. Why did you choose to make “The Colditz Story”?

As a young boy, I always liked the escape stories of the first World War. In the second World War, I wasn’t an escapee, but I always had a soft spot for POW stories, and in that period, there was a tendency to make them rather very sad with the wives and sweethearts at home, things like that. “The Colditz Story” needed a light touch because although it was very dramatic, it was comical. I wanted to pay tribute to all those nations who made fun of the Germans; they made the biggest mistake ever to think that putting all the naughty boys in one camp would solve the problem. “The Colditz Story” was produced by Ivan Foxwell, the first of four pictures we made together. One of the other films we made was “A Touch of Larceny” [1959] which I enjoyed very much. He brought it to me, and at first, it was a very serious story, but I thought it should be a comedy because it was a funny idea. So we made a comedy thriller out of it. I have a soft spot for that picture because I enjoyed working with James Mason very much; it was a very enjoyable picture for me. His co-star George Sanders was huge fun, but he always felt acting was a dreadful thing. I remember I wanted to alter a line or something, and I said, ‘George, can we sit down for a minute?’ He picked up his script, but he only had four pages. He said, ‘I only keep my part, and every time I finish a shot, I tear up the page and throw it away, so now I only got four more pages to shoot and that cheers me up.’ He was not a happy man, he didn’t really enjoy acting. I had a piano on the set for him because he took absolutely no interest in the filming—he was very impeccable and he always knew his lines—but he would go off in the corner, and played a sort of gentle cocktail music till we called him. So while we were preparing the next shot, we always had pleasant music in the background.

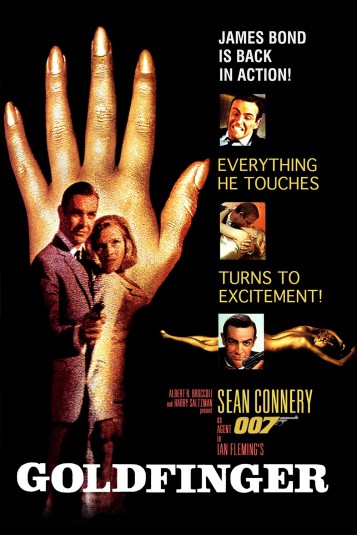

Is it correct to say that the early 1960s, when you made your James Bond films, were a turning point in your career? After all, “Goldfinger” [1964] served as a blueprint for many espionage films and TV series which surfaced in the mid and late 1960s, and it also elevated 007 from a popular hero to the first international screen phenomenon, I suppose?

Is it correct to say that the early 1960s, when you made your James Bond films, were a turning point in your career? After all, “Goldfinger” [1964] served as a blueprint for many espionage films and TV series which surfaced in the mid and late 1960s, and it also elevated 007 from a popular hero to the first international screen phenomenon, I suppose?

It was a very interesting time. I was even asked to do the first James Bond, “Dr. No” [1962]. A lot of people turned it down, and so did I—things came up and I couldn’t go to Jamaica. When I was asked to do “Goldfinger”—the script was very good—I said, ‘Yes.’ But I saw two problems: there was a danger that Bond would become a sort of a Superman. You’ve got to get the best villains in the world because Bond is going to get as good as his villains. Another thing, the script was too Americanized, so I had to make sure all the English scenes became more English. I liked the idea of an intellectual villain. A Bond villain has to be intellectually equal and a worthy opponent of Bond, because he always has a certain scheme in mind and is able to talk about it intelligently. He can’t be a thug; for all the thuggery, he has other people to deal with. Later on, the producers came to Los Angeles and asked me to do “Thunderball” [1964], and at first, I thought that I had run out of ideas for another Bond. After one Bond, you should walk away from it, charge your batteries, and then come back if you have something to say. I felt I didn’t have that, and to do Bond justice, you have to arrive with a huge amount of enthusiasm. The only other Bond I wanted to make was “On Her Majesty’s Secret Service,” back then scheduled with Sean Connery and Brigitte Bardot. Bond gets married, he’s got a beautiful Goddess, and they’d be a great couple. Unfortunately, the picture didn’t work out the way they wanted it to be.

That’s right, since George Lazenby and Diana Rigg played these roles, with Peter Hunt directing. But pretty soon, you were approached again to do “Diamonds Are Forever” [1971]?

That’s right, since George Lazenby and Diana Rigg played these roles, with Peter Hunt directing. But pretty soon, you were approached again to do “Diamonds Are Forever” [1971]?

Yes, and originally planned with John Gavin as Bond. But then Sean Connery decided to come back, and one of the interesting things was that because of Sean’s return, the editor ran into difficulties. Originally the script was scheduled at about 2 hours 30 minutes, but in America, they’d lose one show, possibly two shows each day where they began at 10 am, then another one at 12, 2, 4, 6, 8, and at 10 pm. So when I got to sign my contract, the picture had to be under two hours, or else I had a penalty clause you had never seen in your life [laughs]. But I had a great continuity lady who knew me, she knew my style, and I trusted her timing—she had timed the script. During rehearsals, I always asked her, ‘How long have I got for this scene?’ I really had to control myself. A director has to rely on his continuity lady for quite a number of things. She sits by the camera the whole time, makes notes of every shot, how many takes there are, what costumes the actors wear, the position of everyone, and everything on the set,… So if one person walks out of the room, and the exteriors are shot two weeks later, she has to make sure the actor is wearing the same clothes and looks exactly the same as he did before, even if he got sunburned in the meantime. She takes notes of everything that happens on the set so that the cameraman and the director have something to refer to. Anyway, originally, the producers had planned to shoot “Diamonds Are Forever” entirely at Universal Studios, but we wound up in Las Vegas, which cooperated tremendously well. We convinced them that, if we had a film unit there, it would be good for the city. That wasn’t too difficult to do, and once they were convinced, the town absolutely opened up for us. I had asked them, ‘Suppose I want to shoot in downtown Vegas for four or five nights—because there’s all that free lighting, which is terrific—and we’ll do a car chase. Let’s do in Vegas what we can’t do in Picadilly Circus.’ And it worked. They closed downtown Vegas for five nights which was very tough because shops had to be closed and we were going to run cars up on the pavements. The people in Vegas were as good as their word, and we were able to shoot all the sequences we wanted in downtown Vegas which I don’t think you can do now.

“Diamonds Are Forever” turned out to become one of Bond’s best films, didn’t it?

Well, I enjoyed Bond, I enjoyed the whole experience of Bond and after “Diamonds Are Forever,” I said, ‘Bye-bye and thank you!’ But they said, ‘Oh no, wait a minute, you are to do the next Bond without Sean!’ And so we went off with Roger Moore. I had told him, ‘Whatever you do, don’t try to play Sean Connery. You got to create your own Bond, and I will try and help you because I know the things you’re good at and the things you’re not so good at.’ Every actor has strengths and weaknesses, and as a director you’ve got to find that balance. Roger created his own Bond with a lighter tone than Sean Connery, but that’s because it’s very much his personality. When we were shooting “Live and Let Die” [1973], you could notice that Roger was beginning to relax into the part gradually, no longer cautious that he was competing another Bond. He was beginning to feel Bond in the skin and understood how he had to play it. Halfway through the picture, he was much more relaxed than in the first part of the picture, I think. So I don’t regret returning to Bond with “Live and Let Die,” what I do regret is doing one more Bond after that, “The Man With the Golden Gun” [1974]. But I was quite intrigued with the Bond franchise, and I enjoyed working with [screenwriter] Tom Mankiewicz. We would talk all day and then have to really get down to work. We were always looking for what I call snake pits—this is the most fun, putting Bond in the snake pit, in mortal peril, and at the same time play fair with the audience: how does he get out of it? Then we’d try to find a way to give him fifty seconds to get out of there. It’s funny, we needed three months and were beating our brains out, trying to think of the answer, and the audience gets fifty seconds [laughs]. So when Bond gets out of the snake pit, everybody cheers. We had several terrific snake pit situations, but in some cases, we were never able to find a satisfactory way to get out of it, to find out how Bond could get out of it in a very ingenious way. Occasionally we mailed each other with a solution. We still do; it’s a hobby [laughs]. In “Diamonds are Forever,” for example, we had one we liked, with Bond inside a coffin—who’s got the answer, how is he going to get out of this one? The flames are burning, so you got another five seconds. The answer we came up with, satisfied us.

“Diamonds Are Forever” (1971, trailer)

How do you compare your early Bond films to the ones made today?

Now we see nothing but explosions and bang-bangs, and the stunts are not really very interesting with the trick photography; the FX man is always on top of it. When we did stunts, the stuntman jumped out of a six-floor window into a wet sponge, and if he missed the sponge, he could seriously hurt himself. But at least you knew he jumped. Sean Connery and Gert Froebe played scenes, that’s what I don’t see in the latest Bond films. You’ve got to set a problem for Bond, you’ve got to talk about something.

How did you work on the set? Any agonies you had to cope with?

I always worked very hard on all the scripts, and the picture is in my mind before I go on the floor. You start working with a clear idea, but that doesn’t mean you’re stuck with it. When I’m on location, for example, and I spot, let’s say, a wonderful staircase which can be very useful in a particular scene, I may know how to stage it, but if the dialogue is too short for me to go from the top of the stairs to the bottom, I need maybe ten more seconds of dialogue. The leading lady can say, ‘By the way, remember we have been invited for dinner tomorrow night.’ ‘Oh, I shall remember that, dear.’ And there you got it, you got the shot. So you must be on the set with a clear idea of what you’re up to. Then sometimes things just don’t work out but you must learn to cope with that; in your mind, you know there must be twenty setups that day, or shoot a scene in twenty setups. You go off to a slow start, and somehow you get to lunchtime, and you only did eight setups.There’s no way you’ll do twelve in the afternoon. So what do you do? You can say, ‘Don’t worry, I’ll pick it up.’ But you won’t because as long as you’re on that set, they can’t strike it at night—they got to strike that set to build another one. So during lunch, you got to figure out which of those twelve setups you can do without—will it compromise the picture? These are the nervous decisions you live with for twelve weeks. Carol taught us a lot and all sorts of tricks that were helpful whenever we were in trouble. For example, if a telephone is going to ring, any normal, conventional filmmaker wants to get on with it, and they make sure it will ring. In a quickie, a telephone rings and they make sure the phone’s way over there, so that I have to walk [picks up the phone], ‘Yes? Ah, just a second, it’s for you!’ And then you get up, and you answer the phone—and that’s another minute! [laughs]. I remember on a Carol Reed film, it was in the afternoon, I said to him, ‘Carol, you know we got four more setups to do, and it’s already 4 o’clock.’ And he said, ‘No, it’s not four o’clock, it’s three twenty! Oh no, my watch has stopped!’ Which is typical Carol. Then he’d say, ‘Put some tracks down here, and we’ll get four setups in—and I exaggerate—in half an hour.’ That’s the little technique Carol used when he got behind; he used to lay a pair of tracks and immediately did two or three setups. He was perhaps the most underrated film director in Britain. He did not like message films, although he was a born storyteller but he didn’t get personal views, political or social, across, and I felt very strongly about that. Carol Reed was a great humanist, interested in human behavior, a great disciplinarian who didn’t fall in love with his own work.

What is, in your opinion, a very difficult aspect in the whole process of filmmaking?

To get a picture green-lighted. It’s always difficult for everybody because whoever is allegedly in charge is absolutely terrified. He knows he is only there for a pretty short time before he gets bruted out, and it becomes a revolving thing. The script goes to the sales department [laughs]. ‘Who wants to see a picture about so-and-so?’ Then it goes to the publicity department, and so on. None of this you’re told. I mean, on the last film David Lean was supposed to do, “Nostromo,” he was not very well, and the insurance company insisted there’d be a stand-by director in case he had any problems in the middle of production. I was engaged as that stand-by director. So I spent a few months in the South of France with David. Then he got very sick, the picture was never started, and shortly thereafter, he departed this earth. That was the last time I saw David. “Nostromo” was scheduled to be financed by Spielberg. When David put the script in, Spielberg said, ‘It’s terrible. You can’t make this, David.’ David came back to Europe; he hadn’t done anything for five, six years until a nice French producer wanted to make a deal. So even a man like David Lean couldn’t get anything done. It is the front office that runs it all. Can it be a franchise? No, I don’t think it can be a franchise.

What about the influence and the power of the audience?

What about the influence and the power of the audience?

I never let the audience dictate what picture I should make. If you got a story you want to make, make it the way you think it should be. Don’t let the audience tell you how to make a picture. You should take the audience into consideration all of the time; you’re working for them. Am I clear enough in my storytelling, am I too subtle? Carol and I once did a wonderful thing when shooting a film. We had these two darling old cleaners at the studio. If ever we got into a discussion, he always sent for them. There’s a scene in “A Touch of Larceny” we used with James Mason and George Sanders, who was going to pour poison in some whisky. There was a bottle with ‘poison’ written in large letters. In the scene, James Mason and George Sanders don’t like each other very much and George Sanders chats and pours out a drink for James Mason. So after they have seen the scene, I put the lights up and said, ‘Did you notice anything missing?’ Carol said, ‘The word poison is written so big, you don’t need that.’ I turned to the cleaning ladies, and they said, ‘Oh, he poured a really big one. It was Scotch, wasn’t it? It was brown!’ They were so busy looking at the quantity, it didn’t occur to them to read the label. There are things when you got to think about the audience and their reactions too, but them telling how to make a picture, that’s another story.

How would you compare Carol Reed with David Lean?

Carol Reed was full of humor, while David was very upset about the reception of “Ryan’s Daughter” [1970] and it took him many years before he worked again, and even “A Passage to India” [1984] wasn’t what he had hoped for. He cared about his reputation terribly and was nervous about making that film. He was the opposite of Carol Reed, who went from movie to movie. If the audience didn’t like it, of course, he was sad, but he was able to get on. David’s criticism to Carol was that he made a lot of pictures that weren’t worthy of him. But nothing ever killed my enthusiasm and my passion. I know that I’ve made some bad pictures, but when I was making a film, I knew I had to do the best I could with the material that I was working with. Sometimes I wished I had a more cooperative or a better writer, but that’s the same for everybody.

What would you consider a real nightmare for a director?

The day when you get in the cutting room. Music lengths must be given, the premiere of the film is set, and as always, your time in the cutting room is much too short, but basically that’s as good as it gets. There are always scenes that you never quite solved. Then you come to dubbing, a pretty dull process because you run the reel again and again while the sound technicians rehearse the balance between music, effects, and dialogue. And there you see a sequence that you never quite solved the way you hoped to, and suddenly it strikes what you should have done. You turn to your editor and say, ‘You know, we are idiots, if only we could have done this or that!’ But there you are; you’re absolutely powerless. It’s too late. You carry that into every picture; at some stage later, you know what you should have done, and you didn’t do it. I can watch any of the Bonds I was involved in, and I can enjoy certain scenes. I like scenes that may be meaningless to the audience, but they were a problem for me, and I solved it, I think, elegantly. There are other scenes of which the audience might say, ‘Oh, we loved that scene!’ which may have been so easy to shoot that it was no challenge at all. And then there are scenes when later you realize what you should have done, the mistake that you made. You walk out and go. Sometimes if it’s a premiere, you come back, and you’re amazed that the audience is still there [laughs]. You’d have imagined that they’d all be yelling and booing because they’d have spotted the awful thing that you have done. I get no pleasure out of seeing any of the films I have done because they all contain some of those elements.

Puerto Andraitz, Mallorca, Spain

May 24, 2003

+ Mr. Hamilton passed away on April 20, 2016, at age 93, in a hospital in Palma de Mallorca, near Puerto Andraitz, where he had resided since the early 1970s.

FILMS

UNTEL PÈRE ET FILS, UK title: THE HEART OF THE NATION (1943) DIR Julien Duvivier THIRD ASST DIR Guy Hamilton PROD Paul Graetz SCR Julien Duvivier, Marcel Achard, Charles Spaak. CAST Louis Jouvet, Raimu, Michèle Morgan, Suzy Prim, Renée Devillers; Charles Boyer (narration US version only)

THEY MADE ME A FUGITIVE, US title: I BECAME A CRIMINAL (Warner Bros., 1947) DIR Alberto Cavalcanti THIRD ASST DIR Guy Hamilton PROD Nat A. Bronstein, James A. Carter SCR Noel Langley (novel ‘A Convict Has Escaped’ [1941] by Jackson Budd) CAST Sally Gray, Trevor Howard, Griffith Jones, René Ray, Mary Merrall, Charles Farrell

MINE OWN EXECUTIONER (1947) DIR Anthony Kimmins SECOND ASST DIR Guy Hamilton. PROD Anthony Kimmins, Jack Kitchin SCR Nigel Balchin (also novel ‘Mine Own Executioner’ [1945]) CAST Burgess Meredith, Dulcie Gray, Michael Shepley, Christine Norden, Kieron Moore

ANNA KARENINA (1947) DIR Julien Duvivier ASST DIR Guy Hamilton (Venetian scenes only) PROD Alexander Korda SCR Julien Duvivier, Jean Anouilh, Guy Morgan (novel ‘Anna Karenina’ [1877] by Leo Tolstoy) CAST Vivien Leigh, Ralph Richardson, Kieron Moore, Hugh Dempster, Mary Kerridge

NIGHT BEAT (1947) DIR – PROD Harold Huth ASST DIR Guy Hamilton (location scenes only) SCR T. J. Morrison, Guy Morgan (story by J. T. Morrison) CAST Anne Crawford, Maxwell Reed, Ronald Howard, Hector Ross, Christine Norden.

THE FALLEN IDOL (1948) DIR – PROD Carol Reed ASST DIR Guy Hamilton SCR Graham Greene, Lesley Storm, William Templeton (story by Graham Greene) CAST Ralph Richardson, Michèle Morgan, Sonia Dresdel, Bobby Henrey, Jack Hawkins

BRITANNIA MEWS, US title: THE FORBIDDEN STREET (20th Century Fox, 1949) DIR Jean Negulesco ASST DIR Guy Hamilton. PROD William Perlberg. SCR Ring Lardner, Jr (novel ‘Britannia Mews’ [1946] by Margery Sharp) CAST Dana Andrews, Maureen O’Hara, Sybil Thorndike, Diane Hart, Wilfrid Hyde-White

THE THIRD MAN (Selznick, 1949) DIR – PROD Carol Reed ASST DIR Guy Hamilton SCR Graham Greene (story by Graham Greene, Alexander Korda) CAST Joseph Cotton, Alida Valli, Orson Welles, Trevor Howard, Paul Hörbiger, Ernst Deutsch, Bernard Lee, Wilfrid Hyde-White

THE ANGEL WITH THE TRUMPET (1950) DIR Anthony Bushell ASST DIR Guy Hamilton SCR Clemence Dane, Karl Hartl, Franz Tassié (novel ‘The Angel With the Trumpet’ [1944] by Ernst Lothar) CAST Eileen Herlie, Basil Sydney, Norman Wooland, Maria Schell, Oskar Werner, Anthony Bushell, Wilfrid Hyde-White

STATE SECRET, US title: THE GREAT MANHUNT (1950) DIR Sidney Gilliat ASST DIR Guy Hamilton PROD Sidney Gilliat, Frank Launder SCR Sidney Gilliat (short story ‘Appointment With Fear’ by Roy Huggins) CAST Douglas Fairbanks, Jr., Jack Hawkins, Glynis Johns, Walter Rilla, Herbert Lom

THE AFRICAN QUEEN (United Artists, 1951) DIR John Huston ASST DIR Guy Hamilton PROD Sam Spiegel SCR John Huston, James Agee (novel ‘The African Queen’ [1935] by C.S. Forester) CAST Humphrey Bogart, Katharine Hepburn, Robert Morley, Peter Bull, Theodore Bikel

OUTCAST OF THE ISLANDS (1952) DIR – PROD Carol Reed ASST DIR Guy Hamilton SCR William Fairchild (novel ‘An Outcast of the Islands’ [1896] by Joseph Conrad) CAST Ralph Richardson, Trevor Howard, Robert Morley, Wendy Hiller, Wilfrid Hyde-White

THE RINGER (1952) DIR Guy Hamilton PROD Hugh Perceval SCR Lesley Storm, Val Valentine (play ‘The Ringer’ [1929] by Edgar Wallace) CAST Herbert Lom, Donald Wolfit, Mai Zetterling, Greta Gynt, William Hartnell, Denholm Elliott

THE INTRUDER (1954) DIR Guy Hamilton. PROD Ivan Foxwell SCR John Hunter, Robin Maugham, Anthony Square CAST Jack Hawkins, Hugh Williams, Michael Medwin, George Cole, Dennis Price

AN INSPECTOR CALLS (Watergate, 1954) DIR Guy Hamilton PROD A. D. Peters SCR Desmond Davis (play by ‘An Inspector Calls’ [1946] J.B. Priestley) CAST Alastair Sim, Jane Wenham, Brian Worth, Eileen Moore, Olga Lindo, Bryan Forbes

THE COLDITZ STORY (1955) DIR Guy Hamilton PROD Ivan Foxwell SCR Guy Hamilton, Ivan Foxwell (novel ‘The Colditz Story’ [1952] by Pat Robert Reid) CAST John Mills, Eric Portman, Christopher Rhodes, Lionel Jeffries, Bryan Forbes, Theodore Bikel

CHARLEY MOON (1956) DIR Guy Hamilton PROD Colin Lesslie SCR Leslie Bricusse, John Cresswell (novel ‘Charley Moon’ [1956] by Reginald Arkell) CAST Max Bygraves, Dennis Price, Michael Medwin, Florence Desmond, Shirley Eaton

STOWAWAY GIRL (Paramount, 1957) DIR Guy Hamilton PROD Ivan Foxwell SCR Guy Hamilton, Ivan Foxwell, William Woods CAST Trevor Howard, Elsa Martinelli, Pedro Armendáriz, Donald Pleasence, Warren Mitchell

THE DEVIL’S DISCIPLE (United Artists, 1959) DIR Guy Hamilton PROD Harold Hecht SCR John Dighton, Roland Kibbee (play ‘The Devil’s Disciple’ [1897] by George Bernard Shaw) CAST Burt Lancaster, Kirk Douglas, Laurence Olivier, Janette Scott, Eva LeGallienne

A TOUCH OF LARCENY (Paramount, 1959) DIR Guy Hamilton PROD Ivan Foxwell SCR Guy Hamilton, Ivan Foxwell, Paul Winterton, Roger MacDougall (novel ‘The Megstone Plot’ [1956] by Andrew Garve) CAST James Mason, George Sanders, Vera Miles, Oliver Johnston, Robert Flemyng

THE BEST OF ENNEMIES (Columbia, 1961) DIR Guy Hamilton SCR Jack Pulman (adaptation by Age Scarpelli, Subo Cecchi D’Amico, story by Luciano Vincenzoni) CAST David Niven, Michael Wilding, Harry Andrews, Noel Harrison, Ronald Fraser

MAN IN THE MIDDLE (20th Century Fox, 1964) DIR Guy Hamilton. PROD Walter Seltzer SCR Willis Hall, Keith Waterhouse (novel ‘The Winston Affair’ [1959] by Howard Fast) CAST Robert Mitchum, France Nuyen, Barry Sullivan, Trevor Howard, Keenan Wynn, Sam Wanamaker

GOLDFINGER (United Artists, 1964) DIR Guy Hamilton PROD Harry Saltzman, Albert R. Broccoli SCR Richard Maibaum, Paul Dehn (novel ‘Goldfinger’ [1959] by Ian Fleming) CAST Sean Connery, Honor Blackman, Gert Fröbe, Shirley Eaton, Tania Mallet, Harold Sakata, Bernard Lee, Lois Maxwell

THE PARTY’S OVER (Allied Artists, 1965) DIR Guy Hamilton PROD Anthony Perry SCR Marc Behm CAST Oliver Reed, Clifford David, Ann Lynn, Katherine Woodville, Louise Sorel, Mike Pratt

FUNERAL IN BERLIN (Paramount, 1966) DIR Guy Hamilton PROD Charles D. Kasher SCR Evan Jones (novel ‘Funeral in Berlin’ [1964] by Len Deighton) CAST Michael Caine, Paul Hubschmid, Oskar Homolka, Eva Renzi, Guy Doleman

BATTLE OF BRITAIN (United Artists, 1969) DIR Guy Hamilton PROD Harry Saltzman, Benjamin Fisz SCR Wilfred Greatorex, James Kennaway CAST Harry Andrews, Michel Caine, Trevor Howard, Curd Jürgens, Kenneth More, Laurence Olivier, Christopher Plummer, Michael Redgrave, Ralph Richardson, Robert Shaw, Susannah York

DIAMONDS ARE FOREVER (United Artists, 1971) DIR Guy Hamilton PROD Harry Saltzman, Albert R. Broccoli SCR Richard Maibaum, Tom Manckiewicz (novel ‘Diamonds Are Forever’ [1956] by Ian Fleming) CAST Sean Connery, Jill St. John, Charles Gray, Lane Wood, Jimmy Dean, Bernard Lee, Lois Maxwell

LIVE AND LET DIE (United Artists, 1973) DIR Guy Hamilton PROD Harry Saltzman, Albert R. Broccoli SCR Tom Mankiewicz (novel ‘Live and Let Die’ [1954] by Ian Fleming) CAST Roger Moore, Yaphet Kotto, Jane Seymour, Clifton James, Geoffrey Holder, Bernard Lee, Lois Maxwell

THE MAN WITH THE GOLDEN GUN (United Artists, 1974) DIR Guy Hamilton PROD Harry Saltzman, Albert R. Broccoli SCR Richard Maibaum, Tom Mankiewicz (novel ‘The Man With the Golden Gun’ [1965] by Ian Fleming) CAST Roger Moore, Christopher Lee, Britt Ekland, Maud Adams, Hervé Villechaize, Clifton James, Bernard Lee, Lois Maxwell

FORCE 10 FROM NAVARONE (American International, 1978) DIR Guy Hamilton PROD Samuel Z. Arkoff, Oliver A. Unger SCR Robin Chapman (story by Carl Foreman, novel by Alistair MacLean) CAST Robert Shaw, Harrison Ford, Barbara Bach, Edward Fox, Franco Nero, Carl Weathers, Richard Kiel

THE MIRROR CRACK’D (Associated Film Distribution, 1980) DIR Guy Hamilton PROD John Barbourne, Richard Goodwin SCR Jonathan Hales, Barry Sandler (novel ‘The Mirror Crack’d’ [1962] by Agatha Christie) CAST Angela Lansbury, Geraldine Chaplin, Tony Curtis, Edward Fox, Rock Hudson, Kim Novak, Elizabeth Taylor

EVIL UNDER THE SUN (Universal, 1982) DIR Guy Hamilton PROD John Barbourne, Richard Goodwin SCR Anthony Schaffer (novel ‘Evil Under the Sun’ [1941] by Agatha Christie) CAST Peter Ustinov, Jane Birkin, Colin Blakely, Nicholas Clay, James Mason, Roddy McDowall, Sylvia Miles, Diana Rigg, Maggie Smith

REMO WILLIAMS: THE ADVENTURE BEGINS (Orion, 1985) DIR Guy Hamilton PROD Larry Spiegel SCR Christopher Wood (novel ‘The Destroyer’ by Warren Murphy, Richard Sapir) CAST Fred Ward, Joel Grey, Wilford Brimley, J. A. Preston, George Coe

TRY THIS ONE FOR SIZE (1989) DIR Guy Hamilton PROD Sergio Gobbi. SCR Sergio Gobbi, Alec Medieff (novel ‘Try This One for Size’ [1980] by James Hadley Chase) CAST Michael Brandon, David Carradine, Arielle Dombasle, Guy Marchand, Mario Adorf

You must be logged in to post a comment.