I always thought “Every Day” (2018) was one of the most underrated films released last year. Dealing with an unconventional relationship between the film’s heroine, an ordinary high-school girl, and a lost soul who takes over the mind and the body of a different teenager every day, I had been looking forward to this romantic fantasy ever since it was first announced, knowing it would be directed by Michael Sucsy.

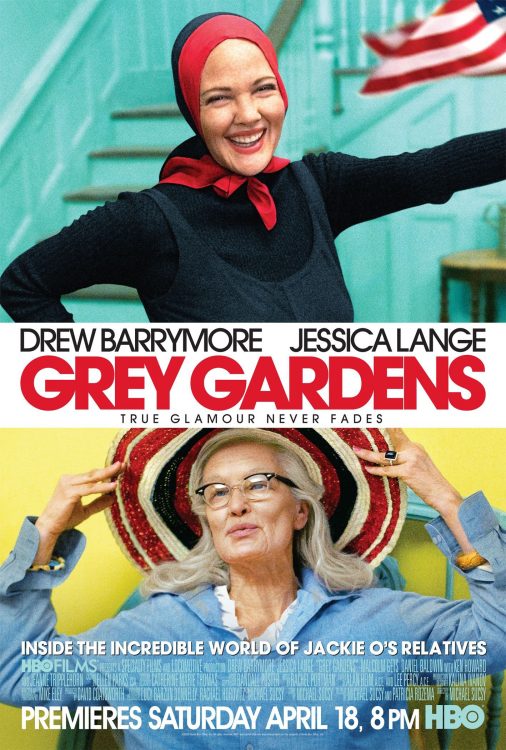

After all, let’s not forget that his debut film was HBO’s highly acclaimed “Grey Gardens” (2009), a mesmerizing drama with Jessica Lange and Drew Barrymore playing Edith Bouvier Beale and daughter Edith—aunt and cousin of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis—which he directed, co-wrote and co-produced, and which earned him multiple awards, including a Golden Globe and an Emmy for Best Motion Picture Made for Television, as well as a Best Actress Golden Globe and Screen Actors Guild Award for Drew Barrymore, and a Best Actress Emmy for Jessica Lange.

“Grey Gardens”—a great example of storytelling on film—is streaming on HBO GO and HBO NOW.

“Grey Gardens” (2009, trailer)

Nevertheless, even though released on a small scale, “Every Day” didn’t lose its appealing charm and innocence. Considering his previous screen efforts—”Grey Gardens” was followed by the romantic drama “The Vow” (2012), starring Channing Tatum and Rachel McAdams, which grossed $125 million in the U.S. and over $200 million worldwide, Mr. Sucsy (b. 1973) put himself on the map right away when he began directing his first films while he was in his mid-thirties. And up until now, not too many filmmakers can say they were that successful right from the very start, in terms of both critical acclaim and box office receipts.

Yet, it then took Mr. Sucsy six years before a new movie of his would hit the screen, but non ce problema. To me, he always makes the right choices at the right time: each and every one of his films is an enriching and rewarding experience, a real joy to the eye. Why? Because within the time frame of each of his movies, you really get to know the characters, you can identify with them, you can appreciate them—you don’t have to agree with what they say or do, but they’re very human, and you can recognize the values they all share. His films make sense and are all the more worthwhile, especially considering that in an era of superhero movies filled with special effects and CGI—there’s absolutely nothing wrong with that!—Mr. Sucsy’s primary focus is time and time again on his story, his characters, and his actors, making him a film director pur sang.

I had the honor of meeting him at his office in Los Angeles to talk about his films, his approach, and his craft, but what I got in return was a most inspiring masterclass by an enthusiastic and gifted filmmaker.

Mr. Sucsy, when I first saw “Grey Gardens,” it was an incredible revelation to me, knowing this was your first film. You’re truly a great actor’s director, aren’t you?

Mr. Sucsy, when I first saw “Grey Gardens,” it was an incredible revelation to me, knowing this was your first film. You’re truly a great actor’s director, aren’t you?

I love working with actors. It’s not the only part of the filmmaking process that I love, but it starts with the actors, and that’s where my heart is.

How did this passion come about?

I was born in New York City but grew up in Connecticut where, for several years, my mother was President of the Board of Directors of the Hartford Stage Company—a very well-regarded regional theater. I often attended opening nights with my parents, so through that, I had a lot of exposure to really great acting while I was still a kid; I was like eleven or twelve at the time. But it goes farther back than that. When my parents were moving out of my childhood home and downsizing, they found a box of my school papers in the attic that included a school composition notebook from when I was about 6 or 7 years old. My classmates and I had an exercise of writing back and forth with our second-grade teacher so we could learn correspondence and communication. Anyway, the first thing I wrote to her was to ask what our class play was going to be. She said she didn’t know yet (to her credit, it was the first week of the school year), and so a few days later, I asked about it again. And then again and again until she made a decision. The play we eventually performed was ‘The Wizard of Oz,’ and the thing I remember most about it had to do with the set, which was a painted backdrop that was an aerial view of the yellow brick road—like a circle or a spiral. And I recall that it bothered me how it looked. It’s clear now that I wanted it to look more realistic, but of course, at the time, I didn’t know what “perspective” was and didn’t express it that way. It’s fun, decades later reading that notebook and realizing that I had an innate interest and love for plays and acting even then. Sometimes you know at a very young age what you’re interested in and what you will eventually end up doing with your life and your career.

It’s fascinating to hear how you refer to your childhood years when you were still at school. I always compare a teacher with a film director: a teacher knows that all his pupils need a different approach according to their needs, while a film director does more or less the same with his cast and crew when he wants them to deliver their best work?

That’s an interesting question because it’s something I do enjoy: I love getting the best performance out of other people, even if they’re not actors. So whether I’m working with my composer or my costume designer, I love encouraging them to do their best work. But I learned early on that the way a film set is structured, everyone is more or less trained to do what the director asks. So I have to be very careful what I say because if I merely dictate ideas instead of seeking input, they will just fulfill the request without thinking critically about alternative approaches. But when I ask questions in a more collaborative way, I create a space for people to bring ideas to the table, which are often better than my initial thoughts. I never show up with no ideas [laughs], I usually say something like, ‘This is the world; these are the parameters. This is the sandbox; let’s play. Now, how can we make this game great?’ And I don’t want someone to change the game, but I do want to foster the best ideas. So as opposed to saying, ‘I only wanna use this color palette’—because that becomes limiting to the other people, I try to create an environment where other people are engaged and encouraged to contribute ideas.

Does that mean you still might have a structured concept in your mind when you appear on the set?

I show up with an approach, but I’m always happy when somebody exceeds my expectations. The best idea wins no matter whose it is as far as I’m concerned. This applies to working with my actors, too, but I’m admittedly not a fan of improvising dialogue. As a writer, I choose my words carefully on the page, and there’s usually a reason why something is written the way it is. On the other hand, I’m always open to making any scene, any line of dialogue better.

It’s amazing and wonderful how present actors naturally are, how they see the story from their character’s point of view almost exclusively, and not from an omniscient third person point of view of a writer or a director. When it’s just me and the script—me and the movie in my head—I’m viewing the film as a whole, but I’m in a bit of a bubble at that point. But then, when I’m first sitting with an actor discussing the script, it immediately forces me to think about the story from his or her character’s singular perspective. And that’s always revealing to me.

As the director, I see it as my responsibility, my job, to set the parameters: you can operate between these tracks and don’t go outside the lines. I don’t want to dictate one single track that the actors have to stick to—it’s so dull for them, and what do I know? I mean, I have my take, but it’s one perspective. But if you set the parameters and play within this area, then you create a place for people to play and experiment, while on the other hand, you can’t have it so wide that people can do absolutely anything because then there is no vision and things go off the tracks. Jessica Lange would say, ‘Was that OTT?’ meaning ‘over the top.’ And I would say, ‘No.’ And then she’d say, ‘And was that one OTT? Because if it was, I’ll pull it back.’ So I think it’s helpful to find those boundaries and find those limits to where things become over the top—whatever that limit is, too quiet, too big, too broad, whatever the “too” is, and also explore those boundaries. One of the biggest challenges for me is when I only get an actor for a day in terms of his or her shooting schedule or what he—or she—has to do in the movie.

Like you did in “Every Day”?

Like you did in “Every Day”?

That’s right. In “Every Day,” I had fifteen actors playing one character—it was about a soul that travels through different people—so there were a lot of actors that I had for just one day or sometimes half a day. Working on a film is like any relationship or marriage: you know the person’s rhythm, how they understand their character, or what they want to do with it, and you’re hopefully on the same page. And when somebody new comes in, all of a sudden the energy changes: it can be exciting, or it can be disruptive. Sometimes that person works very differently, and I have to adjust; either they follow the way I’m doing it, or I have to adjust to them, or maybe it’s somewhere in between. That certainly happened in “Grey Gardens” a little bit. The studio had made some massive changes to the script very close to shooting, and to maintain my vision, I wasn’t always following exactly the pages as rewritten. I remember when I was often talking during the takes—directing Jessica and Drew off-camera while we were filming—that they never broke character; they were always able to stay right there in the scene. So if I’d be over to the side of the camera talking, they never stopped looking at each other. And then there was an actor who came in for a shorter period, he was in a scene with Drew, but that approach of me talking during the take really didn’t work for him. That was when I realized that different actors need very different things from me.

“Grey Gardens” immediately put you in the spotlight, and both you and the film won numerous prestigious awards. How important were winning a Golden Globe and an Emmy career-wise? I can imagine those were incredible highlights to you as a debuting filmmaker?

The premiere of “Grey Gardens” was in April 2009, the Emmys weren’t until September, and the Golden Globes were in January, so it was a lot of joy spread over almost a year. Winning those kinds of accolades is absolutely a highlight, but there are also those little “wins” like when you get the job, or the studio approves the draft of your script, or you get the actor or the money, you get a start date and a green light. As a director, there’s always something else that you have to do next, so it’s sometimes hard to rejoice in an accomplishment when you’re faced with the next task right away, but you have to remember to celebrate the small victories along the way. But, yes, winning the awards was the biggest moment of joy. It was very validating. Although that’s not the reason as a filmmaker, I do the work; to deny that it’s validating would be a lie. But the accolades are not the only way to feel validated. Even if your film doesn’t get external validation at the box office or by critics or win awards, you can feel that making the film was worthwhile for the process.

And maybe they opened the studio gates and the opportunity to make “The Vow”?

Yes, the producers were a company called Spyglass; they now run MGM. At the time, they had another movie, a rom-com with Katherine Heigl. I was looking for something to do that was present-day, in contrast to “Grey Gardens,” which was a period film; something modern and current, even though I love period films. And my manager gave me the rom-com script, but it just wasn’t the story that I wanted to tell. But he said, ‘[Spyglass] is a good company; Cassidy Lange is a smart executive. You should sit with her.’ So I did, and in the process of that meeting, Cassidy pitched me the story of “The Vow,” which I loved. So when the script was ready, she sent it to me. And that’s how it came together initially.

After “Grey Gardens” you also cast Jessica Lange again in “The Vow,” this time in a supporting role as the mother of Rachel McAdams.

Jessica is a phenomenally gifted actress, so it was such a delight to work with her again on “The Vow” although at first, she wasn’t available. But I kept waiting and hoping it could work out, and it did. It was such a treat to work with her on two such distinctly different characters. Jessica is a master; I love watching her work. She’s a dear friend.

“The Vow” grossed $125 million in the U.S. and $200 million worldwide. I suppose your phone then exploded and everybody wanted to work with you?

Yes, but sometimes it can explode with things that you weren’t looking for. “The Vow” was an original story that happened to a real couple, inspired by a true story. There’s an author named Nicholas Sparks who has written a lot of emotional love stories. Both Rachel McAdams and Channing Tatum had been in movie adaptations of his books [she with Ryan Gosling in “The Notebook,” 2004, directed by Nick Cassavetes; he in Lasse Hallström’s “Dear John,” 2010, with Amanda Seyfried], so people thought “The Vow” was too, even though it’s not. Following “The Vow” I got offers to direct several Sparks adaptations, but that wasn’t my desire. It just wasn’t what I wanted to do next. I got very nervous about getting pigeonholed and only being able to make dramatic romances forever, so I just kept saying no. In retrospect, maybe that was an overreaction, but that’s how it felt at the time. After the financial success of “The Vow,” my head got a little caught up in ‘I can’t do a movie for a smaller budget’ or ‘That movie is good, but nobody will go see it.’ So I had to step back and assess what kind of filmmaker I am and want to be.

So it wasn’t easy to make the right decision as to what projects you would accept or turn down?

I could find many things that I didn’t want to do but had a harder time settling on ones I did. It’s not quite as simplistic as that, but that did happen on some level. On the other hand, there were a series of projects that I poured my heart into developing that didn’t eventually get made. There is so much work a director puts into a project before it’s actually a greenlit movie because if you don’t put the effort, your heart and your soul in it, the film’s not going to come to life by itself. And yet, if you do all of that, and they still don’t come to life, it’s very hard. Not everything you work on goes forward for various reasons. A lot of movie babies die well before they see the light of day. That can take a lot out of you. One of the projects, in particular, that didn’t go took me over a year to get over, so I’m saying that it wasn’t as simple as ‘I didn’t know what I wanted to do.’ But that’s all part of the journey, too. It’s easier for other people to say, ‘This is who this filmmaker is.’ It’s a little harder to do that from the inside. It helps when you can look at your work after you’ve made a few films—if you did one or two, you know what resonates with you when you read a script, but you can’t always say, ‘This is it.’ I mean, I can read a comedy or a period piece that I love—there’s a vast range of things that I react to—but if you’re good at one thing and you’re supposed to do it over and over again, it’s not that fun for me. I need to find something different in each film, but I have to find a common thematic thread that keeps me invested.

From that point of view as a film director, and considering the time and energy you invest in any project, don’t you envy actors who can come in on a project for one day or one week?

Yes, people tend to overlook the time a director invests in a film. There’s a lot of effort required just to ready a film—development that can sometimes take years, then pre-production. After the actual shoot, the next nine months are all about post-production, and then you need to promote it. The time commitment to one project is enormous for a director, so you have to make sure that you’re still going to be in love with that project two, three, or even four years from when you start it. In the case of “Grey Gardens”—seven years. In the case of “Playing to the Gods,” which I just finished writing, seven years already and counting. So if you think of a film like a quick tryst and not a love affair, you’re going to run out of steam. You have to be sure you’re going to have the reserves to make it all the way to the finish line because you can’t stop halfway through.

So “Playing to the Gods” might be your next project?

There are a couple of things that could be next, but it’s something that I have written, and I’m passionately determined to make. It’s about Sarah Bernhardt [1844-1923] and Eleanore Duse [1858-1924], their relationship, and how they inspired each other in a competitive way that changed acting forever. They redefined what great acting is. So going back to how much I love working with actors, it’s kind of “Amadeus” meets “The Favourite.”

Earlier, you mentioned that as a child, you were already inspired by actors and acting, but were there maybe film directors or films that also influenced you in your formative years?

It didn’t work that way for me, although there are, of course, many directors whose work I enjoy. I did go to film school, but that was after I was already working in the film industry, so I had gotten bit by the bug before that. In film school, I had to write about a filmmaker, and I chose Ang Lee, I also really love Pedro Almodóvar, although my movies don’t reflect his work at all. But I love his style and sensibility. Many filmmakers inspire me, but I have always felt that ‘following,’ whether it’s a fashion trend or being ‘the popular kid in the class,’ somehow lacked integrity. So the idea of being somebody’s mimic or a shadow or a poor man’s version of them—or better, being inspired by a mentor and then surpassing them—all of that doesn’t interest me, because I don’t think that way. Of course, I’m inspired buy the work others, but I think I take more direct inspiration from photographers than necessarily from a particular film director. I may love one director for his or her early work and another for their late work, or how this director uses music, and what another director does with their actors or with the camera. Why draw just from only one source? It doesn’t feel right. And also, there are so many different challenges that change from film to film. If I were doing some big, long and complicated opening shot, I might watch every Brian De Palma movie to get inspiration, but I would never copy his shots because he didn’t have the same setting or the same script to deal with. We talked before about creating a forum for my collaborators to bring more ideas forward. When I read about Stanley Kubrick, from what I understand, he had a completed vision in his head about how each scene would be executed, and he made that preconceived vision a reality. He’s an extraordinary filmmaker—he’s incredible—but that’s too rigid of an approach for me. I like to have an idea coming in, but I also want to be reactive and spontaneous to what else is happening at the moment. That said, I often know that I can go the distance with a movie when I see the “finished” film in my head, even when the script isn’t anywhere close. It’s like when you meet a young person, and you just know they’re going to be somebody someday. You know that person has a thing, an “it” factor. That’s how I feel about material sometimes: a book, or a script, it might be not quite there, I don’t even realize it’s not quite there sometimes because I see its potential, the finished movie, but not the way Kubrick saw every single frame or scene or shot. I see it done in its entirety, like a package or a bundle. “Grey Gardens” was like that, “Playing to the Gods” too. It doesn’t happen always, but when it does, I know it’s just a matter of time until everything can catch up to realizing that vision. If you can envision it, then it can be realized. That’s why in French, a filmmaker is a réalisateur, right?

And as a ‘réalisateur’ I also like the choices you make, including your work with Rachel Portman. She’s not only one of the most gifted film composers, but her score for “Grey Gardens” is one of her many highlights to date, isn’t it?

She is great! Rachel was suggested to me by the music supervisor of “Grey Gardens,” and I spoke with her during pre-production, but there wasn’t anything to do until we were further along with making the film. And then, when we were finally ready to bring in a composer in the post-production process, she was no longer available. We tried for weeks and weeks to hire someone to replace her, but I just couldn’t find the right connection with anyone else. Then HBO, much to their credit, decided to wait for Rachel to be available. I flew to Minneapolis, where she was doing a musical. We spotted the movie together, and then I had to wait a month before she could start. When she began working on the score, that was the first time I turned my baby over to somebody else—every other part of the process, I remained involved step by step. So I just had to wait to see what was going to come back. When Rachel shared her piano sketches with me, they were wonderfully beautiful, although it was a lesson in trust [laughs] and learning to turn things over and release control. There’s a lot of trust involved in filmmaking, but it’s hand-in-hand. You’re there for every bit of it, but working with her in the very beginning was something like, ‘Call me in a couple of months.’ [Laughs.] And then things didn’t come back fully orchestrated; they were piano demos when she’d say, ‘This is the melody,’ or ‘This is gonna be in violin.’ But I only heard the piano, so I needed all my imagination. Later, when I worked with her again, that process was more familiar and made sense to me, but since “Grey Gardens” was my first film, this was the first time I experienced that. Then we started orchestrating the demos, which means that in advance of recording with a symphony orchestra, they do it electronically so it sounds close to what it will be, although it hasn’t that same richness of a symphony—it’s somewhere between a piano demo and the final version.

“Grey Gardens,” Rachel Portman’s score

By that time, did she also send you the theme already?

No, I kept saying to Rachel, ‘I think we’re missing one musical theme.’ And she said, ‘I don’t think we are.’ So I thought, ‘Okay, you’ve won an Oscar, I’ve never made a movie before, I don’t want to disagree with you, but I do think we’re missing one.’ I kept insisting on it until she finally said, ‘Okay, let me see what I can do.’ I was going to Prague to meet her and record the full score. We had used all the money and the entire budget for the orchestrated demos, and I thought, ‘We cannot go to Prague until I hear that theme orchestrated.’ I couldn’t just do it off a piano demo. And then, a few weeks later, she sent the piano demo, and I was absolutely blown away: it was exactly what I was looking for, I didn’t need to hear the orchestrated demo anymore. And when we were recording in Prague, she said, ‘Yeah, you were right. We did need another thread.’ [Laughs.] It wasn’t “Little Edie’s Theme”… I don’t remember which one it was, to be honest.

Maybe “Cements the Deal”?

[Hums the theme] I can’t remember it because it gets woven in into many different places… it might have been that. But anyway, the way the symphony recording goes is that basically, you do it over two or three days. You start with the biggest pieces, and then you let people go. You don’t build it up: you just start with the biggest and end up with the smallest, you record in that order—I still get emotional thinking about it. So after the symphony orchestra had warmed up, the way they do before a concert at Carnegie Hall or something, they started playing the biggest piece [sings it], and I just lost it, I just lost it. I started crying; it was so emotional. Working on a score has now become my favorite part of post-production because you don’t bring all of that in until everything else is done and set. I think bad filmmaking or bad directing relies on the music to cover up the mistakes in pacing or emotion or whatever. But if you can watch if a movie works naked, then it will work all the more with beautiful music. And in the case of “Grey Gardens,” when Rachel’s music came in, it didn’t just elevate the film from a B to a B+, I mean it went from a B+ to an A+. The film took an enormous leap forward; it was so thrilling.

What about “The Vow”? How did the scoring on that film go?

What about “The Vow”? How did the scoring on that film go?

It was completely the opposite story. I went to Rachel again, and I told her I was gonna do this epic love story. One of the movies I referenced to in the beginning when I did the movie was “The Way We Were” [1973]. But when we were making the movie, Channing was kind of like a raw guy, his emotions were right there, and all of that big music was like a giant wet blanket on top of the movie. It simply did not work. We were like, ‘Ooh, this is too big.’ We were budgeted for a forty-five-piece orchestra—something like that—and then we thought, ‘Less… less… less’ until we were down to guitars basically; I mean there’s more than just guitars, but much smaller sound. At a certain point, Rachel said, ‘I think we need to bring in another composer to work with me. We need another voice.’ And she suggested Michael Brook, who is also represented by her agent, and Rachel gave back part of her fee to be able to hire him. And it was amazing: very often you see one person replacing the other person, but that’s not at all what happened here. Like I said before, Rachel works from piano demos, then we orchestrate them, and we record as a symphony. Michael works from the other way; these two incredible composers work in opposite directions. They could not have more opposite creative processes. And it was fantastic to watch them at work because Rachel would write a melody and hand it off to Michael, and he would take that melody and turn it into something else. And the end product was this unified sound as if one person did it, but it was done by both of them, through and through. And I couldn’t have done it without both of them.

When you scored “Every Day,” you worked with Elliott Wheeler. Can you tell me something about that?

The post-production on that film was very short; it was a drastically reduced schedule—like a third or a half than what I’m used to. I had never worked with Elliott before, but I loved his work, and I felt that he was the right person for it. Directors typically use temp score when we’re editing—using other composers’ music until we’ve locked picture—and people tend to married to their temp score—it’s called temp love [laughs]—and then when you bring in original music, it’s like, ‘No, it doesn’t sound to what I’m used to.’ A lot of times, it’s hard to get film directors to get accustomed to new music because they become accustomed to what they’ve been listening to for six months. But in this case, it was the opposite. I wanted something different from my temp score. Elliott was composing original music, but it was too similar to my temp. So I told him, ‘I hired you for you, so I want more of you in this [score].’ And he was shocked, I think, at first. Like I said, most times, composers find themselves fighting a director who has fallen in love with the music that somebody else wrote.

Because our schedule was so tight, it got down to the point that if we didn’t have a breakthrough by the end of the week, I was going to have to fire him and hire somebody else because we were running out of time. And right at that point [snaps his fingers], Elliott had a breakthrough creating something totally different and fresh. It was like inventing something new as opposed to something derivative. His voice came out, instead of him interpreting another’s voice, and it was great. And again—boom!—it elevated the movie in a way that music should elevate a film. It was thrilling, and he told me later that this process of being pushed ended up reinvigorating his passion for his craft. I wasn’t doing it to do that per se, but it made me proud. I was just trying to get a great movie score out of Elliott, and in the process, ended up making Elliott a better version of himself at that moment. What a thrill that was for me. And now we’re working together again, this time on an original musical.

It was the same thing with Drew, who really pushed herself in playing Little Edie and ended up garnering a lot of praise for her work, including several significant awards, and maybe with Channing too. His character’s name in “The Vow” is Leo, and he told me after watching the film, ‘You got a really good Leo out of me.’ So I’m very proud of collaborating, not only with the actors—and maybe it is easier to witness with the actors because the behind the scenes people are literally behind the scenes—but it’s such a great feeling to have that sense of flow with people, firing on all cylinders.

“Every Day” (2018, trailer)

When you are writing a screenplay, working with your cast and crew, preparing a scene, or whatever, are you aware that your work goes straight to the heart?

When I made “Every Day” our shooting schedule was very short, and our days were too because our lead actress was a minor and in every scene. So I meditated every day before we began filming, so I felt connected to the flow, what the movie needed, and what each moment was about. I was feeling more than I was thinking my way through making that picture. My DP had said before we started principal photography, ‘Don’t bother shot-listing, or you’re just going to get frustrated that you’re not getting what you want,’ so I took his advice. I mean, we had some shots planned out, but a lot of time, we had to adjust very quickly and figure out what we could shoot in whatever time we had left. If I didn’t feel connected to my heart and my soul, I couldn’t have done that. So that’s why I made sure I stayed connected that way. And it’s something I have continued since the shoot and will do going forward, even for films where I do get enough time to pre-plan my shots and coverage.

Fred Zinnemann once told me, ‘I like people to be entertained, but I don’t want it to be empty. I like to give some nourishment.’ That’s exactly what you do in your films, I think.

I’m glad you see that. There was a time when I was unsure if I was making the right decisions or not about the material. I was being sent all kinds of scripts that were very commercial but empty, in my opinion, and I just couldn’t engage with them. But then some of them would go on to make a ton of money, and I’d wonder, ‘Gee, did I make a mistake?!’ But I didn’t because I couldn’t have ever done it well if I didn’t believe in it. It wouldn’t have made money if I had made it without heart. Somebody else connected to that material, and it was the right thing for that person to do. So I’m not judging at all the movie or the director who made it, I’m just saying that for me that it wasn’t a match. I mean if everybody in the world wanted, say, to be married to the same person, that would be a problem. It’s precisely the same thing with material: the right material and the right filmmaker usually find each other. It’s not like ‘These are movies that are worth being made’ and ‘These are movies that are not.’ But for me, in terms of my priorities and my values, it is essential that I feel that it’s nourishing and entertaining for me to want to engage.

Like “The Vow,” which is a perfect combination of nourishment and entertainment, although it’s not really a commercial film on the surface, is it?

It’s still a pretty commercial movie—it’s definitely not an art-house movie. You know, my aunt is a big fan of mine [laughs], she was even before I was a filmmaker, she’s a wonderful woman, and she’s full of love. She just loved “The Vow” and talked about it all the time, she got all of her friends to see it, and her hairdresser saw it a couple of times too and couldn’t stop talking about it. So finally, her husband said, ‘Fine, fine, fine, I’ll go see it.’ After he had seen it, he told her, ‘I’m gonna be a better man to you.’ You affect one person that profoundly, and all the effort I pour into my work is all at once worth it.

Could you ever have expected that “The Vow” would become such a blockbuster?

No. One thing that I didn’t appreciate when I was making the film was how young of an audience it ended up being marketed to.

Did you have any demographics that you could look into?

Yes, and what I mean by that, because it is about a married couple, I wasn’t sure if a young audience would appreciate the nuances and complexities of that situation without having experienced it. But the way that the movie was marketed—it attracted a much younger audience than I expected. When I did “Grey Gardens,” I knew that HBO puts out great content, but they’re not marketing to over/under twenty-four-year-old male/female, it’s not that sort of marketing strategy; they don’t put out that kind of a model. “The Vow” was released by Sony, and they did an incredible job. For instance, I showed the entire movie at the studio for the first time and immediately afterward walked across the lot and to the marketing department, and the trailer was completely cut, with a Taylor Swift song. I said, ‘What?’ I mean, this was 2012, Taylor Swift was so very young then. So I was like, ‘Seriously?’ [Laughs.] But it was a genius idea; it is their job to market the film; they quickly understood the marketplace and made the right choices for it. So it surprised me, yes, but it was a very successful strategy. In the end, people in their twenties, thirties, and forties appreciated the movie too, but younger audiences—teenagers—were absorbed in it. That was interesting.

Were there any sneak previews before the film was released?

Yes, one of the great things about working with the big studios: they test their movies with an audience and collect a lot of very specific data and feedback on the film, which allows you to make it better. For films like “The Vow” the marketing dollars are used to target women over men, because I guess they’ve determined it’s a waste of resources to try to get men into a romance, which I think is sexist and unfortunate, but that’s how marketing romances seems to work. Anyway, when we screened the movie and got the audience’s feedback, the scores from the men were only two or three percentage points lower than from women—which were extremely high. I love that! I don’t make movies for just one kind of person; I make movies for people generally—men and women, young and old. I don’t have final control over what music the marketers put in the trailer, but I do have control over what music I put into the movie, and I don’t want to put in a whole bunch of bubblegum tracks that are going to appeal to young girls, just because it’s a romance. That’s only going to alienate a male audience, why would anyone do that? So try to find a balance, because like I said, I’m making movies for people, all people.

“The Vow” (2012, trailer)

That’s the essence? That’s who you are?

Right! I really love what I do, and it’s very challenging. People have no idea how many movies don’t get made and how much effort goes into projects that never see the light of day. It can be very hard to keep the fire burning, but I do it because I feel I was born to do this. That part of my job is tough and can be disheartening sometimes, but the process of actually making a movie is just so wonderful and thrilling. The other meaningful part is to be able to have a voice that reaches across the globe. It’s almost daunting to think about it, but to have a megaphone as filmmakers do that our voices are amplified in that way, is an awesome responsibility. A director is involved in every single aspect of filmmaking, so there’s no way that you—whoever you are—aren’t going to get woven into the fabric of it. It just happens; you don’t even have to try, it happens.

Los Angeles, California

March 22, 2019

FILMS

EVERY DAY (2018) DIR Michael Sucsy PROD Paul Trijbits, Christian Grass, Anthony Bregman, Peter Cron SCR Jesse Andrews (novel by David Levithan) CAM Rogier Stoffers ED Kathryn Himoff MUS Vladi Slav, Elliott Wheeler CAST Angourie Rice, Justice Smith, Jeni Ross, Lucas Jade Zumann, Rory McDonald, Katie Douglas, Jacob Batalon

THE VOW (2012) DIR Michael Sucsy PROD Paul Taublieb, Jonathan Glickman SCR Abby Kohn, Jason Katims, Marc Silverstein (story by Stuart Sender) CAM Rogier Stoffers ED Nancy Richardson, Melissa Kent MUS Rachel Portman, Michael Brook CAST Rachel McAdams, Channing Tatum, Jessica Lange, Sam Neill, Jessica McNamee, Wendy Crewson, Tatiana Maslany

SCRUPLES (2012) DIR Michael Sucsy PROD Steve Ecclesine TELEPLAY Mel Harris (created by Mel Harris, Bob Brusch; book by Judith Krantz) CAM Rogier Stoffers CAST Jessica McNamee, Chad Michael Murray, Claire Forlani, Mimi Rogers, Boris Kodjoe, Gary Cole, Lindsay Wagner

GREY GARDENS (2009) DIR Michael Sucsy PROD David Coatsworth EXEC PROD Michael Sucsy, Rachel Horovitz, Lucy Barzun Donnelly TELEPLAY Michael Sucsy, Patricia Rozema (story by Michael Sucsy) CAM Mike Eley ED Alan Heim, Lee Percy MUS Rachel Portman CAST Drew Barrymore, Jessica Lange, Jeanne Tripplehorn, Ken Howard, Kenneth Walsh, Arye Gross, Louis Ferreira, Daniel Baldwin

DEEP IMPACT (1998) DIR Mimi Leder PROD Richard D. Zanuck, David Brown PROD ASSISTANT Michael Sucsy SCR Bruce Joel Rubin, Michael Tolkin CAM Dietrich Lohmann ED David Rosenbloom, Paul Cichocki MUS James Horner CAST Robert Duvall, Téa Leoni, Elijah Wood, Vanessa Redgrave, Morgan Freeman, Maximilian Schell, James Cromwell, Jon Favreau, Blair Underwood, Derek de Lint

THE SIEGE (1998) DIR Edward Zwick PROD Edward Zwick, Lynda Obst PROD ASSISTANT Michael Sucsy SCR Edward Zwick, Lawrence Wright, Menno Meyjes (story by Lawrence Wright) CAM Roger Deakins ED Steven Rosenblum MUS Graeme Revell CAST Denzel Washington, Annette Bening, Bruce Willis, Tony Shalhoub, Sami Bouajila, Lianna Pai, Mark Valley, David Provall, Lance Reddick

JUNGLE TO JUNGLE (1997) DIR John Pasquin PROD Brian Reilly PROD SECRETARY Michael Sucsy SCR Raynold Gideon, Bruce A. Evans (screenplay UN INDIEN DANS LA VILLE [1994] by Philippe Bruneau, Hervé Palud, Thierry Lhermitte, Jean-Marie Pallardy) CAM Tony Pierce-Roberts ED Michael A. Stevenson MUS Michael Convertino CAST Tim Allen, Martin Short, Lolita Davidovich, David Ogden Stiers, JoBeth Williams, Sam Huntington, Bob Dishy

You must be logged in to post a comment.