Danny Boyle (b. 1956) is one of the most celebrated filmmakers of his generation. He’s known for his dynamic storytelling, energetic direction, and versatility across genres. With a career spanning over three decades, he has earned critical acclaim and popular success for films ranging from gritty dramas to exhilarating thrillers. His ability to infuse visual flair with emotional depth has made him one of the most distinctive voices in contemporary cinema.

Raised in Manchester in a working-class Irish Catholic family, he originally considered becoming a priest, and ultimately pursued a career in the arts, studying English and Drama at Bangor University in Wales. His early work in theater and television—particularly with the BBC—helped him hone his directorial skills and laid the groundwork for his later success in film.

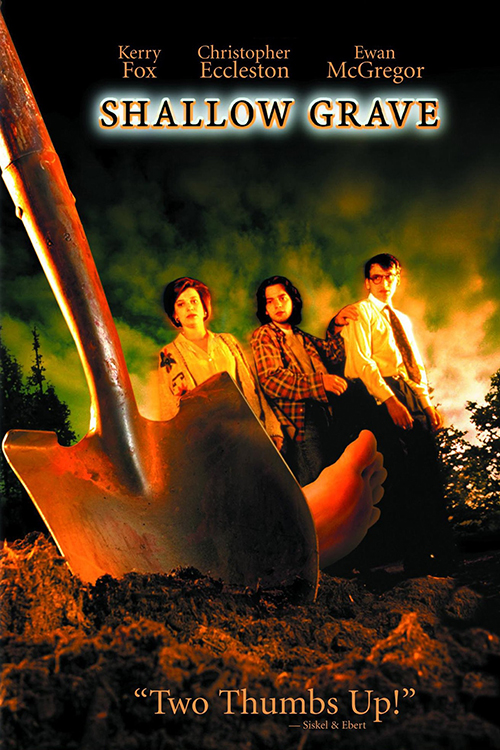

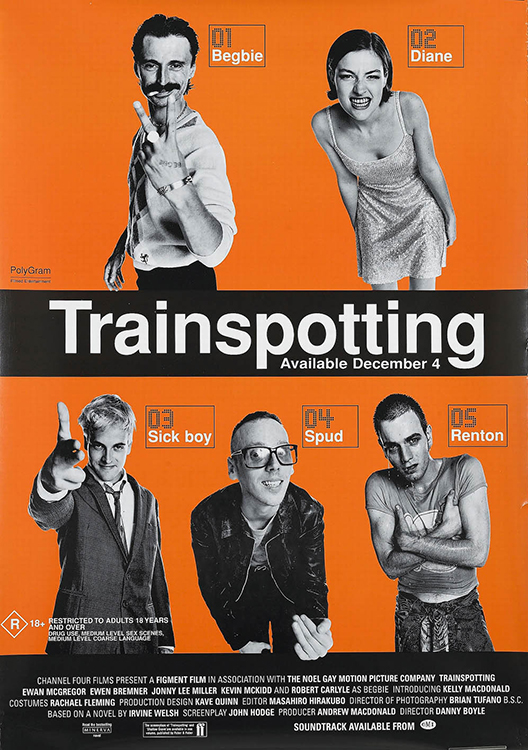

Boyle first gained international recognition with his debut film and BAFTA Award winner for Best British Film, “Shallow Grave” (1994), a stylish thriller about three flatmates who find a dead body and a suitcase full of cash. The film’s tight direction and dark humor attracted critical praise and marked Boyle as a young and rising talent. His breakthrough came with “Trainspotting” (1996), an adaptation of Irvine Welsh’s novel about heroin addicts in Edinburgh. Starring Ewan McGregor in their first of four films together, the film became a huge hit and a cultural phenomenon. Boyle’s kinetic camera work, bold use of music, and raw portrayal of addiction made the film an instant classic; by then, his reputation as a filmmaker who’s not afraid to tackle difficult subjects with flair and intensity also became his trademark.

Boyle first gained international recognition with his debut film and BAFTA Award winner for Best British Film, “Shallow Grave” (1994), a stylish thriller about three flatmates who find a dead body and a suitcase full of cash. The film’s tight direction and dark humor attracted critical praise and marked Boyle as a young and rising talent. His breakthrough came with “Trainspotting” (1996), an adaptation of Irvine Welsh’s novel about heroin addicts in Edinburgh. Starring Ewan McGregor in their first of four films together, the film became a huge hit and a cultural phenomenon. Boyle’s kinetic camera work, bold use of music, and raw portrayal of addiction made the film an instant classic; by then, his reputation as a filmmaker who’s not afraid to tackle difficult subjects with flair and intensity also became his trademark.

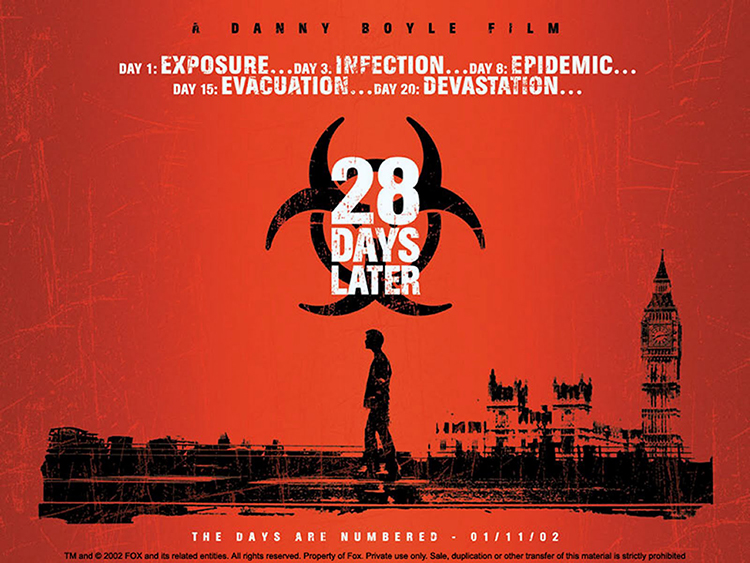

After experimenting with Hollywood in films like “A Life Less Ordinary” (1997) and “The Beach” (2000), filmed in Thailand, Boyle returned to his independent roots with the sci-fi horror “28 Days Later” (2002), a critical and commercial success that revitalized the zombie genre with its fast-paced ‘infected’ concept and digital video aesthetic, influencing later horror films and TV series like “The Walking Dead” (2010-2012). The film’s themes of societal breakdown and survival resonated deeply in a post-9/11 world.

He continued to showcase his eclectic interests with “Millions” (2004), a heartwarming children’s film; renowned American film critic and Pulitzer Prize winner Roger Ebert awarded “Millions” a rating of four out of four and wrote in his March 17, 2005, review that ‘[screenwriter Frank Cottrell] Boyce and [director Danny] Boyle have performed a miracle with their movie. This is one of the best films of the year.’

“Millions” (2004, trailer)

His next film, “Sunshine” (2007), was a cerebral science fiction thriller about a space mission to save Mother Earth, and a compelling and ambitious film that mixed grand, high-concept sci-fi with a deeply human story. It was visually stunning, emotionally intense, and thought-provoking. While its tonal shifts could alienate some viewers, it still remains a standout film in the genre for its exploration of the human condition in the face of an apocalyptic crisis. It’s a film that stays with you, leaving you contemplating the power of the Sun, our place in the universe, and the cost of survival.

Perhaps Boyle’s greatest triumph came with “Slumdog Millionaire” (2008), a rags-to-riches story set in Mumbai. The film won eight Academy Awards, including Best Director for Danny Boyle, and Best Picture. Its blend of vibrant visuals, fast-paced editing, and emotional storytelling resonated with audiences worldwide. The film marked a turning point for cross-cultural cinema by blending Bollywood sensibilities with Western narrative structures, and showed the vibrancy of Indian culture while also addressing poverty, destiny, and resilience. Its critical and worldwide commercial success opened doors for more international storytelling in mainstream cinema.

Danny Boyle wins the Best Director Oscar for “Slumdog Millionaire” at the 81st Academy Awards on February 22, 2009, at the Kodak Theatre in Hollywood

He continued to challenge himself with a wide variety of projects. “127 Hours” (2010), for instance, was a harrowing true story of survival, starring James Franco as a mountaineer who amputated his own arm to escape being trapped by a boulder. The film was praised for its innovative direction and visceral storytelling, earning Boyle two Oscar nominations for Best Picture and Best Writing (Adapted Screenplay). In 2012, he was the artistic director for the Summer Olympics opening ceremony; it was a vibrant, theatrical celebration of British history and culture watched by over a billion people.

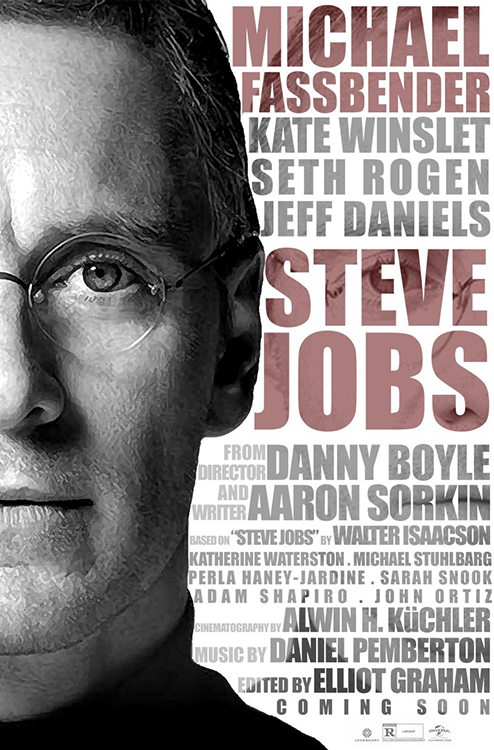

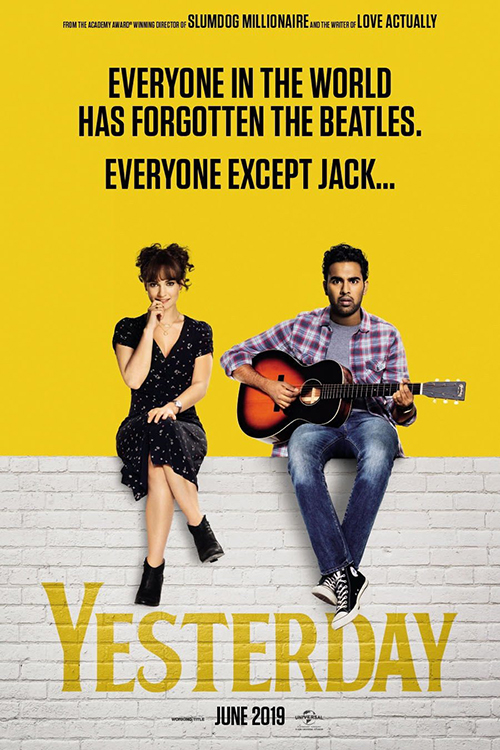

In more recent years, Boyle has remained active with projects like “Steve Jobs” (2015), a stylized biopic written by Aaron Sorkin and starring Michael Fassbender, and “T2 Trainspotting” (2017), a reflective sequel to his 1996 hit. He also directed “Yesterday” (2019), a heartwarming tribute to The Beatles, and a whimsical musical romantic comedy based on the premise that only one man, a struggling musician, remembers The Beatles after a global blackout, and becomes famous for performing their songs. Made for $26 million, the film grossed $155 million worldwide.

Danny Boyle’s work is marked by a relentless curiosity and a refusal to be pigeonholed. Whether dealing with addiction, horror, science fiction, or real-life drama, his films often explore the resilience of the human spirit and the unpredictable nature of life. With his signature energy, visual inventiveness, and emotional resonance, Boyle remains one of the most influential and exciting directors in contemporary cinema.

Over the years, he was considered or asked to direct films like “Scream” (1996), “Alien: Resurrection” (1997), “The Full Monty” (1997), “Fight Club” (1999), “American Psycho” (2000), “X-Men” (2000), “8 Mile” (2002), and “No Time to Die” (2021), but for various reasons he didn’t or couldn’t.

“28 Years Later” (2025, trailer)

The fourteen feature films he directed up until now have grossed over $1 billion worldwide (source: Box Office Mojo), making him a highly profitable filmmaker, especially considering he’s known for working with relatively tight budgets—preferably less than $20 million per film—to make sure he has full creative control over his projects. His latest film, “28 Years Later,” the sequel to “28 Days Later,” was an exception; budgeted at $60 million, it’s his most expensive film so far. As of this month, the film is available in theaters in most territories.

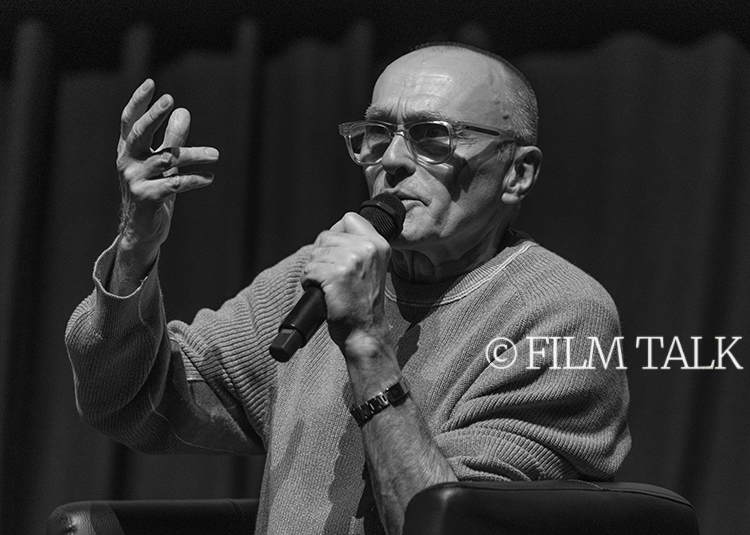

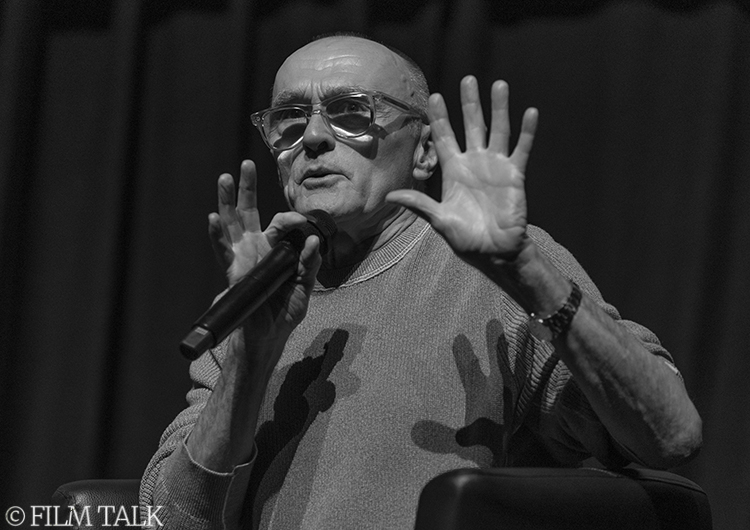

Last April, Danny Boyle was the guest of honor at the Brussels International Fantastic Film Festival for the third time, after he visited the Festival to promote the release of “Shallow Grave” (1994) and “28 Days Later” (2002). During the Festival’s 43rd edition last April, he did a Q&A. As the BIFFF is a genre film festival, the conversation dealt mostly with his genre films.

The Q&A, as you can find here, has been edited and condensed for clarity.

With “T2: Trainspotting” [2017] and now “28 Years Later,” you made a few sequels. Do you sometimes have reservations about sequels?

It’s the story that matters, really. You need to come up with a decent story that you really want to tell. When you finish a film, you tend to feel like you told the story, and you don’t want to go back to it. But if you have a good idea and a good story… there is also a commercial aspect to it, especially these days when it’s getting more and more difficult to raise the money for a different kind of film. It’s a lot easier to make something when it’s attached to an intellectual property and an idea that has an attraction to the audience. But you do it because the story gets you and when it’s different from the original movie, so it will be worth your while to see it. What you don’t want to do is just repeat the first film. There are obviously things that are the same, but there is an evolution and there are a lot of different things that are involved. This film [“28 Years Later”] cost a lot more because you can no longer claim poverty and ask people to work for very little money. You want to pay people quite rightly. So it cost a lot more than the original movie, but we tried to keep the spirit of it. We used a series of cameras including iPhones which gave us a flexibility we didn’t have in the first film that was shot with digital cameras—the first film was the first widely released digital film, apparently—so you keep the spirit through that and apply it in a different way. It’s not an urban film; the first film is very much an urban film set in a city, obviously, principally, but now we stayed out of cities and towns, and filmed in the Northeast of England, above Yorkshire. A wonderful, beautiful place.

When you made your first film, “Shallow Grave” [1994], did you have full autonomy on the set?

We raised a million quid to make that film in thirty days, and Channel Four gave us the money, but they put in a guy—understandably from their point of view—on the set to keep an eye on us. We didn’t get along with him at all. It was quite tense, really. Anyway, on the third day of filming, we spent all morning to get a shot but couldn’t get it, and this guy rang Channel Four and said, ‘We’re gonna be hugely behind. I think you should replace the director.’ We had a stooge at Channel Four who told us this, so we rang Channel Four and said, ‘We want to sack this guy.’ ‘Okay, you can sack him, but if you fall behind, we will sack you.’ So we went on and finished on time, but in the end, we ran out of money; we spent all of our money on our set—the flat. We had no money to do the police scenes that we shot on the last day, so we sold off bits of the set and the furniture to buy more celluloid.

Looking back at “28 Days Later” [2002], was it a difficult film to edit?

No. We had an amazing editor called Chris Gill. He loved editing it, much more so than the normal process of enjoying your job or whatever. He loved the texture of the shoot because it was shot on this very high shutter angle, and the way it interacted with the video camera, it gave this very high edge to things which suits his editing style. So he’d constantly be chopping back and forwards. Some of these things you can see in it, and some are almost invisible. It really suited his style of editing.

“28 Days Later” was your first of five films—so far—written by Alex Garland. Can you tell something about him?

He writes very cinematically, and when he turned up with the script of “28 Days Later,” we did some work on it and then we decided to make it. He writes very quickly; like John Hodge, he thinks about it for a long time, and then writes very quickly. For those of us who can’t really write, it’s incredible because he can literally write a script in a weekend. I’m not good at writing dialogue; I like the structure of the material and the way it expresses itself, but for me, it’s very difficult to write dialogue that humanizes the characters. I can do the structure of a scenario, and I love doing that, and that’s how I tend to work with writers when we work on a script. But I know my limitations, for sure.

The scene of walking through a deserted London is a seminal scene in your films.

It was a very different time; we shot that in July 2001, and the reason I remember that is not because I have a great memory, it’s because we shot it very early in the morning, and the weather was great. You’re only able to shoot for a couple of hours in London at that time; there’s enough light, it’s just dawning, so it’s a beautiful light, there’s nobody around, just a few ravers coming out of clubs who find it very entertaining that a film is being made. And we had this clever idea to use very pretty girls to stop the traffic. If you get the police to stop the traffic, you have to pay a lot of money. We didn’t have that money, but what we were allowed to do was to request the traffic to stop. We were allowed to ask drivers, ‘Would you mind waiting here?’ So we had a lot of pretty girls, including my daughter, to ask the traffic to stop. They just leaned into the cars, ‘Excuse me, would you mind waiting here for a minute?’ And we could shoot the sequences, so we were very fortunate to do that, including shooting near Downing Street. I remember we nearly finished shooting a scene and then a security guy came along. He said, ‘What are you doing here?’ I said, ‘We have permission to work here.’ ‘But I can’t find a permission anywhere.’ I remember saying, ‘Oh, that’s a terrible mistake. I’m so sorry.’ ‘Yeah, you’d better hurry up and finish it! You should leave here!’ If you do that now, you get shot because two months later, 9/11 happened. It weirdly flipped the film into a different focus when it came out. It was the first film that approached a kind of mass sense of panic, and vulnerability, like the vulnerabilities of cities especially. Previously they were ever-expanding, they weren’t ever gonna stop, build bigger and bigger, more and more people in it, and suddenly there was this sense of fear in cities which you could grasp from 9/11. Everything changed. That’s one of the reasons why the film resonates with people, I think. Now, safety is so important and dominant as an element when you make films. Everything is checked and has to be supervised by so many people. It’s extraordinary the way that the industry has changed since then.

Cillian Murphy wanders the empty streets of London in “28 Days Later” (2002)

What do you like about making a genre film?

The joy of making a horror film is creating the suspense about something that might happen, and then not being able to predict how it’s gonna happen, or how you’ll be confronted with the forces around you that represent darkness, demons, monsters—whatever you want to think of.

Can you tell something about your background?

I come from a Catholic working-class background in Manchester. I was originally going to be a priest; my mother wanted me to be a priest. I was an altar boy too. And there are many similarities between being a priest and being a director; you’re telling people what to do, how they should be thinking… [laughs]. I went to a seminary which is a training school for priests and a teacher in my school said, ‘Mmm, I don’t think you should do that.’ Then I discovered girls and I ended up going to the University College of North Wales [now called Bangor University] where I first started directing. I found myself in charge, telling people what to do, like, ‘Stand there,’ or ‘Do that.’ Then I got a job in the theater and worked my way up. Later, I worked for the Royal Court Theatre in London, a wonderful place for new writers. It specializes in new writing for the stage with great respect for writers that has been very beneficial in my career. But I didn’t really know the theater; when I got a job in the theater, it was just to earn some money. I always wanted to do cinema, and when I saw a job in Northern Ireland, I got to do one-hour drama films for television.

Any films or filmmakers who influenced you during your formative years?

I remember vividly when “A Clockwork Orange” [1971, directed by Stanley Kubrick] came out. It was banned in the UK, but I saw it before it was banned. That was a fundamental one for me, and “The Exorcist” [1973, directed by William Friedkin] too. As a Catholic, it had an enormous effect on me. Nicolas Roeg was also very important to me, with the way he edited, and the way he presented his material. You know who David Puttnam is? He produced “Chariots of Fire” [1981]; he was a big producer in Great Britain at the time. I wrote to him constantly and never heard back from him. All these people you wrote, you never heard back from them. So my apologies if anybody ever wrote me—that’s just the way it is [laughs].

“Sunshine” [2007] was a science fiction film, also written by Alex Garland. Are you a science fiction fan?

“Sunshine” [2007] was a science fiction film, also written by Alex Garland. Are you a science fiction fan?

I love real science fiction with things that could conceivably happen. I’m not a big fantasy fan as such. There are two divisions; I’m not a “Star Wars” fan, I’m more like an “Alien” man. I got to read the script of “Alien: Resurrection” [1997]; it was a very good script. I remember I went to Sigourney Weaver, which was an extraordinary experience. A very beautiful woman, obviously; a very interesting woman as well. We set out to do it, but I couldn’t work out how to do the CG in it. Those were the early days of CG, but it was obviously moving towards CG—that was the idea—away from the way that Ridley Scott did it, the old-fashioned way of doing it with warriors in a suit, but I couldn’t master the CG. So I lost confidence about doing that, and I pulled out. I couldn’t do it because I wouldn’t do the job very well [the film was directed by French filmmaker Jean-Pierre Jeunet]. There was CG in “Sunshine” outside the ship, but we built everything else for real, in a small studio in East London. We did it for very little money—it looks like it’s a lot more money than it cost which is a tribute to all the people who worked on it, like the designers and the technicians.

Your films are always very successful, except for “A Life Less Ordinary” [1997], a romantic comedy, starring Ewan McGregor, Cameron Diaz, and Holly Hunter. That film didn’t work too well at the box office, except in Belgium. How do you explain that?

There used to be a rule in film distribution—it changed with streaming, I’m sure—if you had a massive hit, there would always be one place where it was a flop and nobody could understand why. Always one territory, like Slovakia, where it was a big flop, and where nobody went to see it. And when you have a huge flop, there’s always one place, like Slovakia, where it’s a huge hit! Maybe it was the title, A life less ordinary; you see that phrase a lot in advertising, or bastardizations when people are advertising their flats, like a flat less ordinary. That was the first time that phrase was ever used. I remember that we said, ‘That’s an insane title!’ It may be one of the reasons that the film was a terrible flop, apart from Slovakia—or Belgium [laughs].

What would you consider to be your best film?

There’s this theory, which I think is basically true, that your first film is always your best film. Of course, you get better as you get more experienced, but you don’t necessarily make better films. Take the Coen Brothers [Joel Coen, Ethan Coen] who have made a series of extraordinary masterpieces, but you can ask yourself if any of their films is better than “Blood Simple” [1984]. Probably not. My Dad used to come along to see all of my films—he passed away after “Slumdog Millionaire” [2008]—and he watched them all. With each film, he’d say, ‘Yeah, it’s good, but it’s not as good as “Shallow Grave.”’

Brussels International Fantastic Film Festival

April 12, 2025

FILMS

SHALLOW GRAVE (1994) DIR Danny Boyle PROD Andrew MacDonald SCR John Hodge CAM Brian Tufano ED Masahiro Hirakubo MUS Simon Boswell CAST Kerry Fox, Christopher Eccleston, Ewan McGregor, Ken Scott, Keith Allen, Colin McCredie, Victoria Nairn, Gary Lewis, Jean Marie Coffey, John Hodge

TRAINSPOTTING (1996) DIR Danny Boyle PROD Andrew Macdonald SCR John Hodge (novel “Trainspotting” [1983] by Irvine Welsh) CAM Brian Tufano ED Masahiro Hirakubo CAST Ewan McGregor, Ewen Bremner, Jonny Lee Miller, Kevin McKidd, Robert Carlyle, Kelly Macdonald, Peter Mullan, James Cosmo, John Hodge, Andrew Macdonald

TRAINSPOTTING (1996) DIR Danny Boyle PROD Andrew Macdonald SCR John Hodge (novel “Trainspotting” [1983] by Irvine Welsh) CAM Brian Tufano ED Masahiro Hirakubo CAST Ewan McGregor, Ewen Bremner, Jonny Lee Miller, Kevin McKidd, Robert Carlyle, Kelly Macdonald, Peter Mullan, James Cosmo, John Hodge, Andrew Macdonald

A LIFE LESS ORDINARY (1997) DIR Danny Boyle PROD SCR John Hodge CAM Brian Tufano ED Masahiro Hirakubo MUS David Arnold CAST Ewan McGregor, Cameron Diaz, Holly Hunter, Delroy Lindo, Ian Holm, Maury Chaykin, Dan Hedaya, Ian Mcneice, Tony Shalhoub, Stanley Tucci

TWIN TOWN (1997) DIR Kevin Allen PROD Peter McAleese EXEC PROD Danny Boyle, Andrew Macdonald SCR Kevin Allen, Paul Durden CAM John Mathieson ED Oral Norrie Ottey MUS Mark Thomas CAST Llyr Ifans, Rhys Ifans, Dorien Thomas, Dougray Scott, Buddug Williams, Ronnie Williams, Huw Ceredig, Rachel Scorgie, Di Botcher, Kevin Allen

THE BEACH (2000) DIR Danny Boyle PROD Andrew Macdonald SCR John Hodge (novel “The Beach” [1996] by Alex Garland) CAM Darius Khondji ED Masahiro Hirakubo MUS Angelo Badalamenti CAST Leonardo DiCaprio, Tilda Swinton, Virginie Ledoyen, Guillaume Canet, Robert Carlyle, Paterson Joseph, Zelda Tinska, Peter Gevisser

28 DAYS LATER (2002) DIR Danny Boyle PROD Andrew Macdonald SCR Alex Garland CAM Anthony Dod Mantle ED Chris Gill MUS John Murphy CAST Cillian Murphy, Naomie Harris, Christopher Eccleston, Megan Burns, Brendan Gleason, Toby Sedgwick, Christopher Dunne, Emma Hitching, Danny Boyle (Infected Running Across Minefield [uncredited])

MILLIONS (2004) DIR Danny Boyle PROD Graham Broadbent, Andrew Hauptman, Damian Jones SCR Frank Cottrell-Boyce (also novel “Millions” [2004]) CAM Anthony Dod Mantle ED Chris Gill MUS John Murphy CAST Alex Etel, Lewis Owen McGibbon, James Nesbitt, Daisy Donovan, Christopher Fulford, Pearce Quigley, Jane Hogarth, Alun Armstrong

SUNSHINE (2007) DIR Danny Boyle PROD Andrew Macdonald SCR Alex Garland CAM Alwin H. Küchler ED Chris Gill MUS John Murphy CAST Rose Byrne, Cliff Curtis, Chris Evans, Troy Garity, Cillian Murphy, Hiroyuki Sanada, Mark Strong, Benedict Wong, Michelle Yeoh, Paloma Baeza, Archie Macdonald, Sylvie Macdonald

28 WEEKS LATER (2007) DIR Juan Carlos Fresnadillo PROD Enrique López Lavigne, Andrew Macdonald, Allon Reich EXEC PROD Danny Boyle, Alex Garland SCR Juan Carlos Fresnadillo, Enrique López Lavigne, Rowan Joffe, Jesús Olmo CAM Enrique Chediak ED Chris Gill MUS John Murphy CAST Jeremy Renner, Rose Byrne, Robert Carlyle, Harold Perrineau, Catherine McCormack, Idris Elba, Imogen Poots, Mackintosh Muggleton

SLUMDOG MILLIONAIRE (2008) DIR Danny Boyle PROD Christian Colson SCR Simon Beaufoy (novel “Q&A” [2005] by Vilkas Swarup) CAM Anthony Dod Mantle ED Chris Dickens MUS A.R. Rahman CAST Dev Patel, Freida Pinto, Madhur Mittal, Anil Kapoor, Irrfan Khan, Saurabh Shukla

SLUMDOG MILLIONAIRE (2008) DIR Danny Boyle PROD Christian Colson SCR Simon Beaufoy (novel “Q&A” [2005] by Vilkas Swarup) CAM Anthony Dod Mantle ED Chris Dickens MUS A.R. Rahman CAST Dev Patel, Freida Pinto, Madhur Mittal, Anil Kapoor, Irrfan Khan, Saurabh Shukla

127 HOURS (2010) DIR Danny Boyle PROD Danny Boyle, Christian Colson, John Smithson SCR Danny Boyle, Simon Beaufoy (book “Between a Hard Rock and a Hard Place” [2004] by Aron Ralston) CAM Anthony Dod Mantle, Enrique Chediak ED Jon Harris MUS A.R. Rahman CAST James Franco, Amber Tamblyn, Kate Mara, Treat Williams, John Lawrence, Aron Ralston

TRANCE (2013) DIR Danny Boyle PROD Christian Colson SCR John Hodge, Joe Ahearne (story by Joe Ahearne) CAM Anthony Dod Mantle ED Jon Harris MUS Rick Smith CAST James McAvoy, Vincent Cassel, Rosario Dawson, Danny Sapani, Matt Cross, Wahab Sheikh, Mark Poltimore

STEVE JOBS (2015) DIR Danny Boyle PROD Danny Boyle, Guymon Casady, Christian Colson, Mark Gordon SCR Aaron Sorkin (authorized self-titled biography “Steve Jobs” [2011] by Walter Isaacson) CAM Alwin H. Küchler ED Elliot Graham MUS Daniel Pemberton CAST Michael Fassbender, Kate Winslet, Seth Rogen, Jeff Daniels, Michael Stuhlbarg, Katherine Waterston

STEVE JOBS (2015) DIR Danny Boyle PROD Danny Boyle, Guymon Casady, Christian Colson, Mark Gordon SCR Aaron Sorkin (authorized self-titled biography “Steve Jobs” [2011] by Walter Isaacson) CAM Alwin H. Küchler ED Elliot Graham MUS Daniel Pemberton CAST Michael Fassbender, Kate Winslet, Seth Rogen, Jeff Daniels, Michael Stuhlbarg, Katherine Waterston

BATTLE OF THE SEXES (2017) DIR Jonathan Dayton, Valerie Faris PROD Danny Boyle, Robert Graf SCR Simon Beaufroy CAM Linus Sandgren ED Pamela Martin MUS Nicholas Britell CAST Emma Stone, Steve Carell, Andrea Risebrough, Natalie Morales, Sarah Silverman, Bill Pullman, Alan Cumming, Elisabeth Shue, Lewis Pullman

T2 TRAINSPOTTING (2017) DIR Danny Boyle PROD Danny Boyle, Andrew Macdonald, Christian Colson, Bernard Bellew SCR John Hodge (novel “T2 Trainspotting” [2002] by Irvine Welsh) CAM Anthony Dod Mantle ED Jon Harris MUS Rick Smith CAST Ewan McGregor, Ewen Bremner, Jonny Lee Miller, Robert Carlyle, Steven Robertson, Irvine Welsh, Kelly Macdonald

YESTERDAY (2019) DIR Danny Boyle PROD Danny Boyle, Richard Curtis, Tim Bevan, Eric Fellner, Matthew James Wilkinson, Bernard Bellew SCR Richard Curtis (story by Richard Curtis, Jack Barth) CAM Christopher Ross ED Jon Harris MUS Daniel Pemberton CAST Himesh Patel, Lily James, Joel Fry, Ed Sheeran, Kate McKinnon, Ellise Chappell, Meera Syal, Harry Michell, Vincent Franklin, Sophia Di Martino, Robert Carlyle

YESTERDAY (2019) DIR Danny Boyle PROD Danny Boyle, Richard Curtis, Tim Bevan, Eric Fellner, Matthew James Wilkinson, Bernard Bellew SCR Richard Curtis (story by Richard Curtis, Jack Barth) CAM Christopher Ross ED Jon Harris MUS Daniel Pemberton CAST Himesh Patel, Lily James, Joel Fry, Ed Sheeran, Kate McKinnon, Ellise Chappell, Meera Syal, Harry Michell, Vincent Franklin, Sophia Di Martino, Robert Carlyle

CREATION STORIES (2021) DIR Nick Moran PROD Ben Dillon, Shelley Hammond, Nathan McGough, Holly Richmond, Orian Williams EXEC PROD Danny Boyle, Kyle Stroud, Compton Ross, Sam Parker, Steven O’Connell, Damien Morley, Will Machin, Ryan R. Johnson, Phil Hunt, Mickey Gooch Jr., Christine Cowin, Chris Cleverly, Natalie Brenner, Greg Barrow, Lee Aaron Bennett SCR Irvine Welsh, Dean Cavanagh CAM Roberto Schaefer ED Emma Gaffney CAST Ewen Bremner, Leo Flanagan, Richard Jobson, Rori Hawthorn, Tess Rowe, Ciaran Lawless, Jack Paterson, Gerry Knotts, James Hicks, Irvine Welsh

28 YEARS LATER (2025) DIR Danny Boyle PROD Danny Boyle, Andrew Macdonald, Alex Garland, Bernie Bellew, Peter Rice SCR Alex Garland CAM Anthony Dod Mantle ED Jon Harris MUS Young Fathers CAST Jodie Comer, Aaron Taylor-Johnson, Ralph Fiennes, Jack O’Connell, Alfie Williams, Amy Cameron, Stella Gonet, Geoffrey Austin Newland

TV MOVIES

SCOUT (1987) DIR – PROD Danny Boyle TELEPLAY Frank McGuinness CAM Philip Dawson CAST Ray McAnally, Stephen Rea, Gerard O’Hare, Colin Connor, Michael Liebmann, Lloyd Hutchinson, Jeremy Chapman, Paul Ryder

LORNA (1987) DIR James Ormerod PROD Danny Boyle TELEPLAY Graham Reid CAST Kenneth Branagh, James Ellis, Mark Mulholland, Gwen Taylor, John Hewitt, Brid Brennan, Julia Dearden, Tracey Lind, Ainé Gorman, Colum Convey, George Shane

THE ROCKINGHAM SHOOT (1987) DIR Kieran Hickey PROD Danny Boyle TELEPLAY John McGahern CAM Philip Dawson CAST Bosco Hogan, Niall Toibin, Marie Kean, Tony Rohr, Oliver Maguire, Ian McElhinney, Hilary Reynolds, John Olohan

THE VENUS DE MILO INSTEAD (1987) DIR Danny Boyle TELEPLAY Anne Devlin ED John Callister CAST Jeananne Crowley, Lorcan Cranitch, Iain Cuthbertson, Ruth McGuigan, Ann Hasson, Trudy Kelly, Aine McCartney, Leila Webster, Tony Doyle

THE NIGHTWATCH (1989) DIR – PROD Danny Boyle TELEPLAY Ray Brennan CAM Philip Dawson ED Roger Ford-Hutchinson CAST Michael Feast, Leslie Grantham, Tony Doyle, James Cosmo, Don Fellows, Sean Chapman, Oliver Maguire

ELEPHANT (1989) DIR Alan Clarke PROD Danny Boyle TELEPLAY Bernard MacLaverty CAM Philip Dawson, John Ward ED Don O’Donovan CAST Gary Walker, Bill Hamilton, Michael Foyle, Danny Small, Robert J. Taylor, Joe Cauley, Noel McGee, Patrick Condren, Andrew Downs

MONKEYS (1989) DIR – PROD Danny Boyle TELEPLAY Paul Muldoon CAM Arthur Rowell ED John Callister CAST Manning Redwood, William Hootkins, Harry Ditson, Clarke Peters, Bob Sherman, Martha Thimmesch

STRUMPET (2001) DIR Danny Boyle PROD Martin Carr TELEPLAY Jim Cartwright CAM Anthony Dod Mantle ED Chris Gill MUS John Murphy CAST Christopher Eccleston, Jenna G., Stephen Walters, David Crellin, Jonathan Ryland, Stephen Taylor, Graeme Hawley, Josh Cole, Adam Zane, Steve Money

VACUUMING COMPLETELY NUDE IN PARADISE (2001) DIR Danny Boyle PROD Martin Carr TELEPLAY Jim Cartwright CAM Anthony Dod Mantle ED Chris Gill MUS John Murphy CAST Timothy Spall, Michael Begley, Katy Cavanagh-Jupe, James Cartwright, Julie Brown, Keith Clifford, David Crellin, Caroline Pegg

DARCEY BUSSELL’S NEW DANCE (2018) DIR Danny Boyle [segment “Emancipation of Expressionism”], Mark Cohen, Eddie Frost PROD Mark Cohen, Martin Collins, Anu Giri, Simon Richardson CAM Brett Turnbull ED Rebecca Bowker, Jon Harris, Ben Millner MUS Jasmin Boivin CAST Darcey Bussell

TV MINISERIES

MR. WOE’S VIRGINS (1993) DIR Danny Boyle PROD John Chapman TELEPLAY (novel “Mr. Woe’s Virgins” [1991] by Jane Rogers) CAM Brian Tufano ED Masahiro Hirakubo MUS Roger Eno, Brian Eno CAST Jonathan Pryce, Minnie Driver, Lia Williams, Kerry Fox, Kathy Burke, Moya Brady, Catherine Kelly, Freddie Jones

BABYLON (2014) DIR Danny Boyle, Sally El Hosaini, Jon S. Baird PROD Derrin Schlesinger TELEPLAY Jesse Armstrong, Sam Bain, Jon Brown (created by Jesse Armstrong, Sam Bain) CAM David Raedeker, Enrique Chediak, Balazs Bolygo ED Jon Harris, Gary Scullion, Mark Davies, Iain Kitching MUS Rick Smith, Stuart Earl CAST Brit Marling, Bertie Carvel, Paterson Joseph, Daniel Kaluuya, Jonny Sweet, Nicola Walker, Stuart Martin

PISTOL (2022) DIR Danny Boyle EXEC PROD Danny Boyle, Craig Pearce, Anita Camarata, Hope Hartman, Steve Jones, Paul Lee, Gail Lyon, Tracey Seaward TELEPLAY Craig Pearce (book “Lonely Boy: Tales From a Sex Pistol” [2017] by Steve Jones, Ben Thompson) CAM Anthony Dod Mantle ED Jon Harris CAST Toby Wallace, Anson Boon, Sydney Chandler, Jacob Slater, Talulah Riley, Maisie Williams, Thomas Brodie-Sangster, Louis Partridge, Francesca Mills

You must be logged in to post a comment.